Attorney General Meese is a living legend. At the age of 92, he has made more contributions to the law than just about any American who did not serve on the Supreme Court. I barely scratched the surface of his remarkable career in my 2022 Meese Lecture. Yet, if you ever meet Mr. Meese (and do not call him General!), you will find a humble and sincere man. Meese is not one to boast about his voluminous accomplishments. Fortunately, two of Meese’s close associates in the Reagan Administration have put pen to paper, and recorded for posterity the Attorney General’s accomplishments.

Steve Calabresi and Gary Lawson have published a new book, titled The Meese Revolution: The Making of a Constitutional Moment. The book tells the story of how Meese revolutionized constitutional law in the Department of Justice, and set the stage for the current originalist majority on the Court. I would highly commend this amazing book, which was released today. (I was able to get a signed copy at the Federalist Society convention last week!)

Beyond the thorough treatment of Meese’s legacy, the book has countless fun tidbits that I enjoyed. One of them concerned the case of Hodel v. Irving (1986). The book describes how Solicitor General Charles Fried had to fight the “deep state” within the SG’s Office. This case presented the question of how broad the government’s taking power was. Gary Lawson, who worked in OLC, favored a more narrow reading of the taking power. But the career lawyers in the SG’s office used a far more capacious term: plenary.

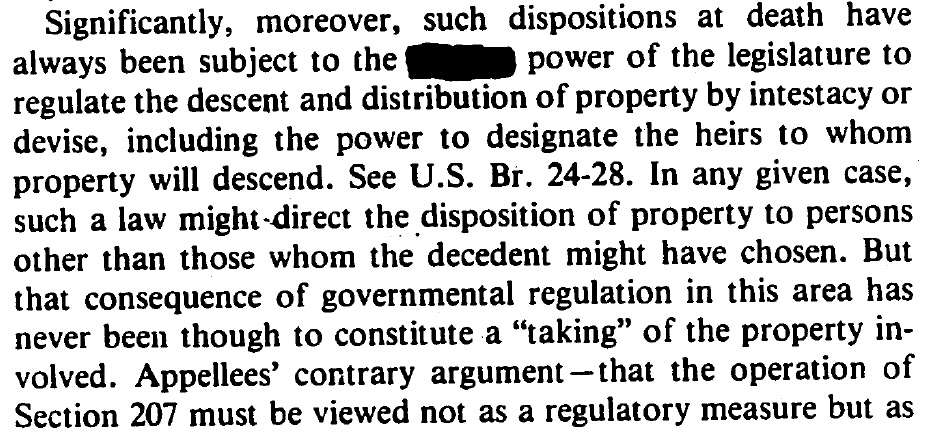

In the early draft brief for Hodel v. Irving, the case involving the Native American lands, Lawson was surprised to see an argument—apparently authored by career SG lawyers Ed Kneedler and Larry Wallace—saying, “Moreover, every sovereign possesses the plenary power to regulate the manner and terms upon which property may be transmitted at death, as well as the authority to prescribe who shall and who shall not be capable of taking it” (emphasis added). Much of this statement was uncontroversial. No one doubts that governments can regulate the passage of property by will; there have long been statutes defining how to write a valid will, limiting to some extent the power fully to disinherit certain family members, and so forth. The key to the draft brief’s argument was the word “plenary.”

However, the political appointees in DOJ objected to the word “plenary”:

In the early draft brief for Hodel v. Irving, the case involving the Native American lands, Lawson was surprised to see an argument—apparently authored by career SG lawyers Ed Kneedler and Larry Wallace—saying, “Moreover, every sovereign possesses the plenary power to regulate the manner and terms upon which property may be transmitted at death, as well as the authority to prescribe who shall and who shall not be capable of taking it” (emphasis added). Much of this statement was uncontroversial. No one doubts that governments can regulate the passage of property by will; there have long been statutes defining how to write a valid will, limiting to some extent the power fully to disinherit certain family members, and so forth. The key to the draft brief’s argument was the word “plenary.”

So what did Fried do? He pulled out a marker and redacted the word “plenary” from the brief:

Recall how Fried mentioned that he sometimes received briefs from his staff with little or no time to make revisions. This time, he received printed copies of the brief—several dozen of them—ready to be filed with the Supreme Court. The brief described the government’s “plenary” power over testation, including its ability to abolish altogether people’s power to pass down their property. There was then no way to make revisions to the briefs; they were in final printed form. Charles Fried found a way. On the eve (literally the eve) of filing the briefs in the Supreme Court, he took a marker and personally, by hand, blacked out the word “plenary” in every printed copy of the brief. Today, when everything is digitized, this remarkable event is in danger of disappearing. But if one can locate a hard copy of the brief (there are nine depositories for printed SG briefs across the country), or a PDF that accurately reproduces the original document, one will see a handmade deletion in every copy. This was Charles Fried at his finest—and the career staff in the SG’s Office doing what it did.

When I read this passage, I immediately emailed the amazing librarians at the South Texas College of Law to find the brief. Fortunately, they have microfiched copies of Supreme Court briefs from the 1980s. And they found the Hodel reply brief:

On page 5 of the brief, you can see the redaction:

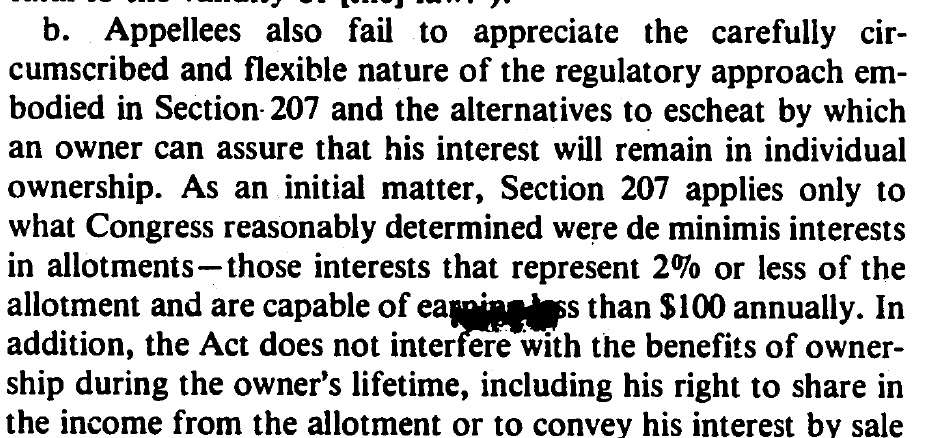

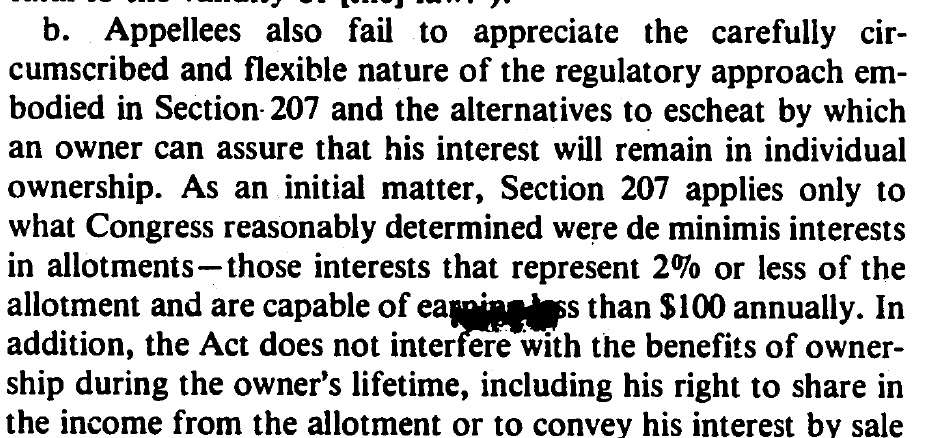

And the marker bled through to page 6:

If you pull up the brief on Westlaw, there are two question marks in the place of the redaction

The story gets even better. Justice O’Connor asked Ed Kneedler about this issue during oral argument:

The story gets even better. Justice O’Connor asked Ed Kneedler about this issue during oral argument:

There is a coda to the story. Even after Fried’s heroic effort at damage control, if one held up the marked-out portion of the printed briefs to the light, one could faintly see the word “plenary” underneath. At oral argument in Hodel v. Irving, when Ed Kneedler presented the government’s case, Justice O’Connor asked, “Mr.

Kneedler was asked about the limits of government power regarding the descent of property belonging to Indians. He was questioned whether the government has the authority to make any kind of regulation, to which he replied that their submission does not go that far. He mentioned that the legislature has broad power over property descent and that it is a privilege that can be conditioned or even abolished. However, he clarified that the Court has never had to address this issue directly. When asked if property transfer at death could be abolished, Kneedler stated that it was not part of their submission in this case. Justice O’Connor further inquired about this possibility, to which Kneedler reiterated that it was not part of their argument. The discussion focused on the limited scope of the law in question in the case.

Source link