Culture is a valuable heritage, much harder to create than to destroy, and once lost, almost impossible to recover.

Commentary

What can we learn from culture?

One important lesson is the realization that we are currently in a critical period, reminiscent of what Karl Marx referred to as a “plastic moment.”

To adapt an old saying: Will England always endure?

This question of stability is on everyone’s minds and in their hearts.

It’s not just England that concerns us.

From the law to the economy, political landscapes to shifts in technology, and the inevitable changes in demographics, America, the West, and the world at large in the early 21st century are facing unprecedented uncertainties.

What we once took for granted is now in question in a fundamental, yet elusive manner.

Doubts emerge regarding our confidence in “the market,” national identity, the foundations of social order, and cultural values.

Predicting cultural trends has become more precarious and hesitant in this current climate.

It’s a recurring theme to assume that present disruptions are unique.

As Edward Gibbon noted in “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” there is a tendency in human nature to downplay current advantages and magnify present evils.

However, history has shown that there are moments when this natural inclination aligns seamlessly with reality.

Is there something distinct or notably different about the economic crisis that began in 2008, was expected to resolve but is persisting or worsening?

Has the ideology of transnational progressivism infiltrated political elites to the extent that it endangers American self-governance and individual freedoms?

Are we on the verge, or perhaps past the brink, of a “fourth revolution” following the American Revolution, Civil War, and FDR’s New Deal—ushering in a new era that will reshape political and cultural life in the country?

These unprecedented circumstances, as Mr. Murray points out, leave us with many uncertainties:

“We have never observed a great civilization with a population as old as the United States will have in the twenty-first century; we have never observed a great civilization that is as secular as we are apparently going to become; and we have had only half a century of experience with advanced welfare states.”

Where does this leave us? In 1911, poet-philosopher T. E. Hulme remarked that “there must be one word in the language spelled in capital letters.”

For a long time, that word was “God” for sane individuals.

Then, the focus shifted to “Reason” for a century, and now many regard “Life” with reverence.

Hulme’s insight on the instinctual reverence and cultural shift is thought-provoking.

One wonders if our focus as a society has transitioned from “Life” to “E” for “Egalitarianism” or “P” for “Political Correctness.”

It is striking to see how certain key terms have diminished in significance.

Take the word “Gentleman,” for instance.

Once a crucial moral and cultural ideal, it has lost its prominence.

What has become of the concept it represented?

Similarly, consider the term “respectable.”

It has transformed into what philosopher David Stove termed a “smile word”—a forgotten virtue we acknowledge but no longer embody publicly.

Though the word remains, its essence has been removed from serious discourse.

Using it straightforwardly is challenging, much like calling someone “respectable” today without a hint of irony.

Leo Strauss humorously noted the evolution of the word “virtue” from denoting manliness to primarily signifying a woman’s chastity.

Today, chastity and manliness are outdated themes in Western culture, viewed with a knowing smile.

Philosopher Harvey Mansfield has explored the decline of manliness and its transition into ironic irrelevance.

The pressing question is: Without the guiding principles of manliness, which underpin cultural confidence, how do we interpret “the lessons of culture”?

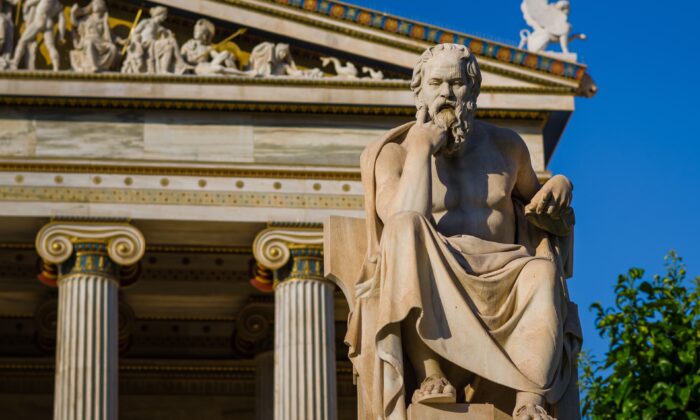

In one of his essays on humanism, T. S. Eliot reflected on distilling the essence of figures like Horace and the Elgin Marbles, stating that for a long time, these symbols were revered for their connection to humanity and culture.

As we navigate the complexities of modern society, with its shifting values and uncertainties, it becomes crucial to preserve and uphold the values and lessons embedded in our cultural heritage.

Francis, and Goethe” the result will be “pretty thin soup.”

“Culture,” he concluded, “is not enough, even though nothing is enough without culture.”

In other words, culture is more than a parade of names, a first prize in the game of “cultural literacy.”

Another lesson concerns the fragility of civilization.

As Evelyn Waugh noted in the dark days of the late 1930s, “barbarism is never finally defeated; given propitious circumstances, men and women who seem quite orderly will commit every conceivable atrocity.”

“The danger,” Waugh wrote, “does not come merely from habitual hooligans; we are all potential recruits for anarchy.”

He went on to warn that “The more elaborate the society, the more vulnerable it is to attack, and the more complete its collapse in case of defeat. At a time like the present it is notably precarious. If it falls we shall see not merely the dissolution of a few joint-stock corporations, but of the spiritual and material achievements of our history.”

It is a prime lesson of culture to acquaint us with those facts. “History,” Walter Bagehot wrote in “Physics and Politics,” his clear-eyed paean to liberal democracy, “is strewn with the wrecks of nations which have gained a little progressiveness at the cost of a great deal of hard manliness, and have thus prepared themselves for destruction as soon as the movements of the world gave a chance for it.”

The moral is this: Culture is a precious inheritance, immeasurably more difficult to achieve than to destroy, and, once destroyed, almost irretrievable.

It’s not at all clear that we have learned the lesson, though wise men from before the time of Pericles have sought to bring us that sobering news.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.