In Old English, your average elf (or ælf or ylfe) belonged on the naughty list: They were malicious, imp-like creatures, blamed for mischief, mayhem and evil.

At the time, another word for a nightmare was ælfadl, “elf-sickness,” and a hiccup was an ælfsogoða, “elf-cough, elf-heartburn.”

In Beowulf, elves (ylfe) are in a list of monstrous races having sprung from Cain’s murder of Abel, and therefore despised by God.

The Proto-Germanic root of “elf” may be one meaning “white”—making it a relative, through its PIE root, of “albino” and perhaps “Alp”— and that’s evident in Norse myth, which described “fair elves.”

Thus, the word “elf” was often used interchangeably with “fairy” beginning in the medieval era, leading to the idea of tall, noble elves: In Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590), the Redcrosse Knight, one of the “Faerie Knights,” is described as “a valiant Elfe.”

This work, along with a host of other Norse and Anglo-Saxon lore, would influence Tolkien’s works.

You may also remember the “elf-lock” from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet—also 1590s—a knot in the hair supposedly tied by Queen Mab, “the fairies’ midwife.” (The precise folkloric inspiration for Queen Mab is hotly debated, but variations of her certainly predate Shakespeare.)

[MERCUTIO:] This is that very Mab

That plaits the manes of horses in the night

And bakes the elflocks in foul sluttish hairs,

Which once untangled, much misfortune bodes.

This is the hag, when maids lie on their backs,

That presses them and learns them first to bear,

Making them women of good carriage.

Ultimately, Christmas elves are a pretty recent concept.

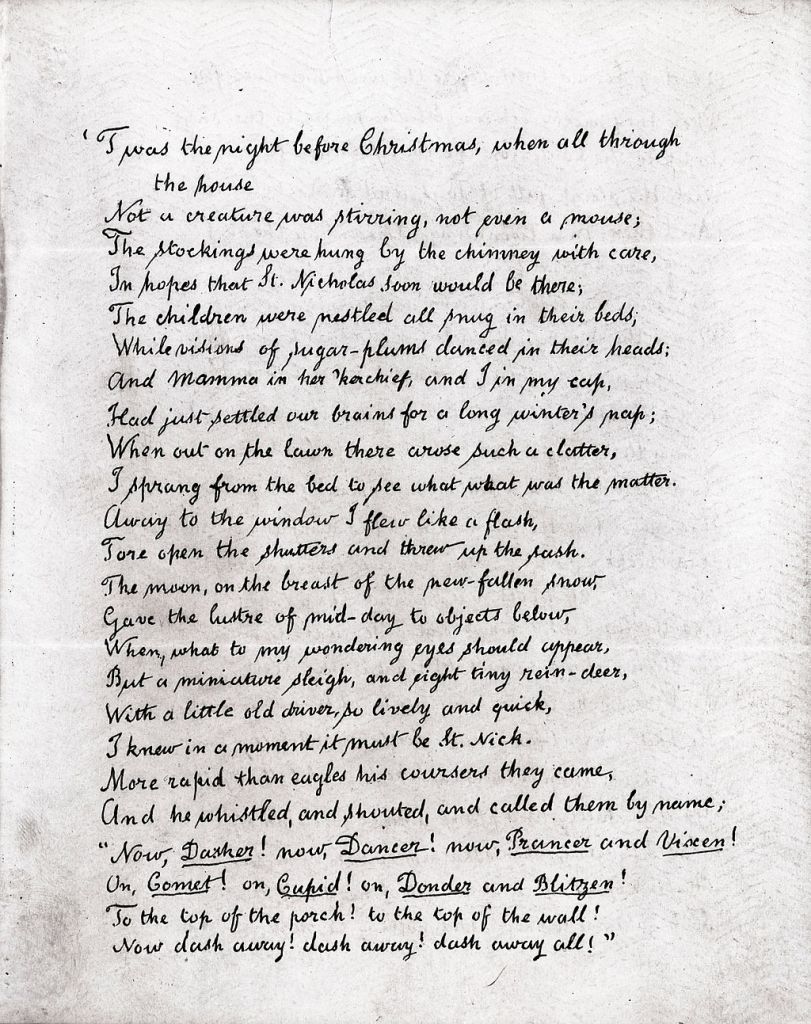

The word “elf” was not specifically associated with Christmas and Santa Claus (or his predecessors) until 1823, in the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” ostensibly written by Clement Clarke Moore, who claimed authorship in 1837.

You might know this work better as “Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

But that poem doesn’t actually mention toy-making elves: It calls Santa himself a “jolly old elf,” simply suggesting that he’s an elf-like fellow because he’s magical and joyful.

It would appear that the contemporary Christmas elf began to appear around the 1850s in American literature.

Little Women author Louisa May Alcott briefly mentioned “Christmas elves” in her children’s short story “A Christmas Dream, and How It Came to Be True,” and evidently completed but never published a book called Christmas Elves.

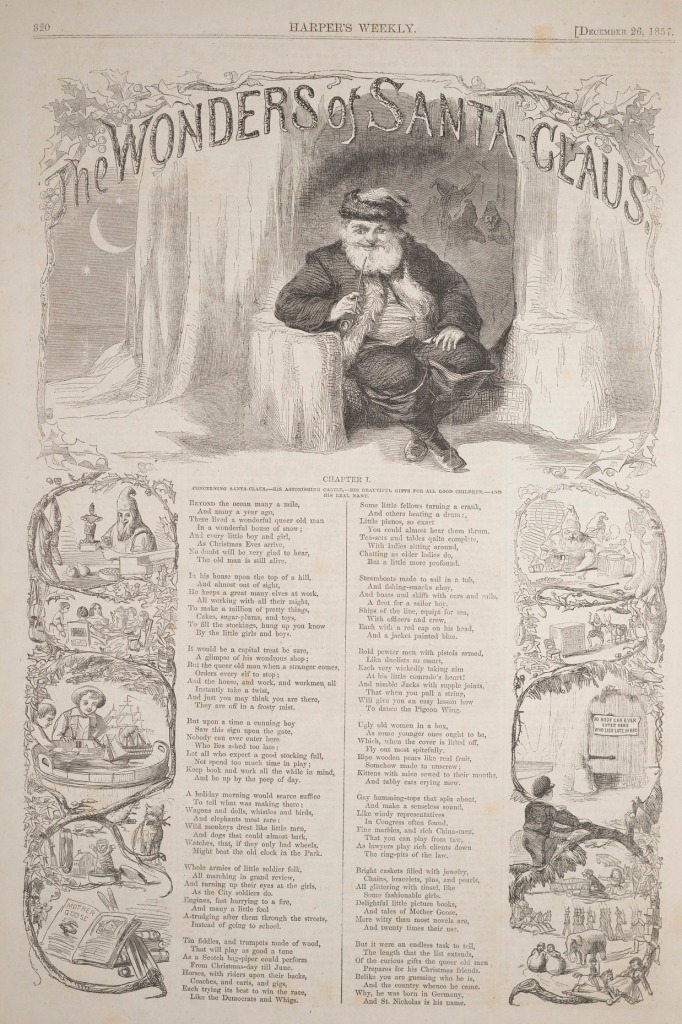

In 1857, Harper’s Weekly published an uncredited poem called “The Wonders of Santa Claus,” which details Santa’s workshop:

He keeps a great many elves at work

All working with all their might

To make a million of pretty things

Cakes, sugar-plums, and toys

To fill the stockings, hung up you know

By the little girls and boys.

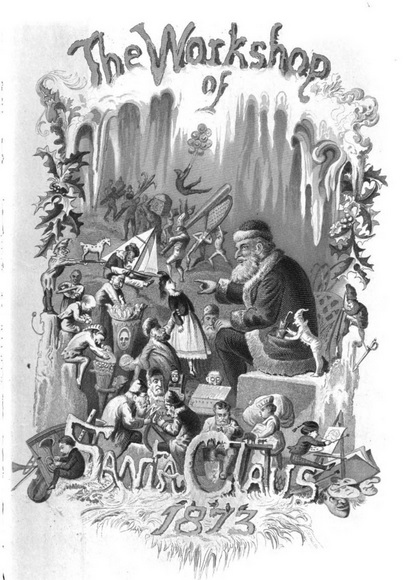

And then in 1873, modern Christmas elves appeared in an illustration on the cover of the highly influential women’s magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book.

It shows a similar image of the workshop—Santa, toys, elves and all—accompanied by the caption: “Here we have an idea of the preparations that are made to supply the young folks with toys at Christmas time.”

Can you please rephrase this sentence?

Source link