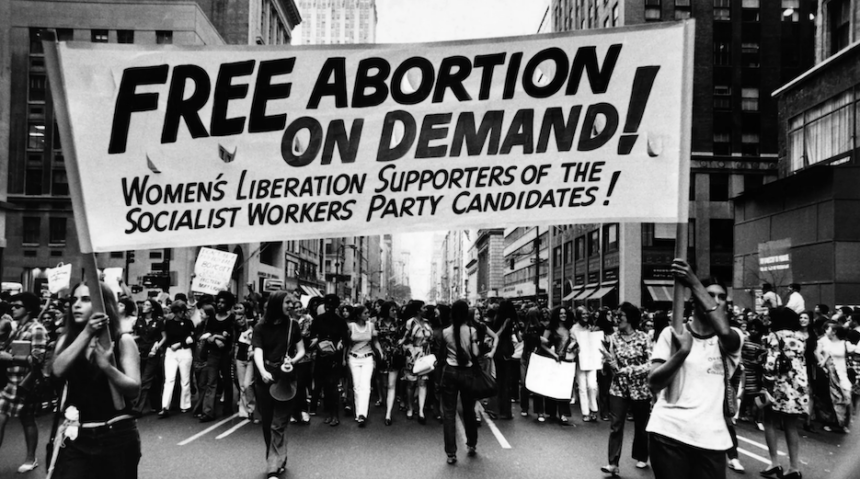

(Image source: Getty Images)

This past February, President Joe Biden offered a muddled statement on abortion. He disavowed “abortion on demand” because he’s a “practicing Catholic” but maintained that “Roe v Wade was right.” The President’s statement spurred a flurry of commentary that puzzled over his position on abortion and what he meant by the phrase “abortion on demand.”

While Biden’s tepid support of abortion rights has been apparent for years, the meaning of “abortion on demand” is less so. Some respondents, like the President of Planned Parenthood, condemned the phrase as “right-wing language.” More nuanced analyses note that the phrase “abortion on demand” originated with abortion rights activists and only later became a conservative phrase to repudiate abortion.

Yet, both perspectives misunderstand the more complicated political history of “abortion on demand” and its connections to religion in general and Catholicism in particular. Moreover, they overlook the fact that the denigration of “abortion on demand” was and remains rooted in sexism that has spanned religious denominations, political affiliations, and both the anti-abortion and abortion rights movements.

Yet, both perspectives misunderstand the more complicated political history of “abortion on demand” and its connections to religion in general and Catholicism in particular. Moreover, they overlook the fact that the denigration of “abortion on demand” was and remains rooted in sexism that has spanned religious denominations, political affiliations, and both the anti-abortion and abortion rights movements.

A primer on the term’s complicated history is necessary, not just to understand President Biden’s utterances, but to better navigate the post-Dobbs landscape.

For over six decades, the struggle over the meaning of “abortion on demand” has reflected the fight over men’s ability to control women’s reproductive lives. In the early 1960s, state legislatures began to reconsider abortion restrictions amidst revelations of the high rates of criminal abortions and in the wake of thalidomide and rubella scares, which led to birth defects and infant deaths. Male medical experts, legal reformers, allied professionals, and religious leaders had an outsized voice in popularizing and shaping the meaning of “abortion on demand” – a phrase so foreign it needed to be put into quotations in expert and popular literature.

Media coverage in the early 1960s linked the foreignness of “abortion on demand” with actual foreign countries’ abortion policies. Japan, Hungary, and the Soviet Union were go-to examples because they permitted elective abortions. American commentators believed the United States was unlikely to adopt such alien practices. Such was the case in 1962, in discussions of the popular book The Abortionist by Lucy Freeman, which saw one of the earliest variations of this phrase in the American press. Amidst Cold War xenophobia, these foreign associations did little to help make the case for abortion on demand in the United States.

The landscape of reproductive rights, however, was rapidly shifting, and the foreign associations of abortion on demand would soon overlap with domestic debates within the growing American abortion rights movement. At first, the abortion rights movement was male-dominated and made up of “small, well-defined groups of elite professionals: public health officials, crusading attorneys, and prominent physicians.” By the mid-1960s, there were two major camps in the abortion rights movement: reformers and repealers. It was these two camps’ division over policy that would play a crucial role in shaping the political meaning of abortion on demand for decades to come.

The difference between supporters of reform and repeal was the degree of change they envisioned to abortion laws. Reformers called for a limited set of exceptions to these restrictions so that “deserving” women could access abortion. Rape, incest, fetal deformity, and the health and life of the mother, they believed, were among the grounds for terminating pregnancies. Repealers, meanwhile, wanted abortion to be elective—a private decision made by any woman for any reason. Abortion rights activists—reformers and repealers alike—used the phrase “abortion on demand” to signal the latter position.

At a moment when abortion laws, at their most permissive, allowed the procedure to save the life of the mother, reformers viewed themselves as political realists. While some reformers privately supported elective abortion, they believed the stigma surrounding the procedure meant that they could only ask for limited changes from state legislatures. Reform leaders like Dr. Alan Guttmacher maintained that the United States was “not ready” for the “abortion on demand” policies that existed in “iron curtain countries” because it would lead to an “ethical uproar.”

(Image source: Abortion On Demand)

What was often left unstated by reformers–because it was taken for granted–was that the ethical uproar had to do with distrusting women to control their reproduction. You can see the mistrust made explicit in a 1967 article by Dr. Eugene M. Diamond, a Catholic anti-abortion physician. Diamond declared that those “who propose abortion on demand” have “an inordinate confidence in the wisdom of the average woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy.” A number of reformers shared similar views about women’s capacity to make reproductive choices. Others strategically sought to appease chauvinistic politicians, physicians, and a wider public by proposing policies that mandated male medical and legal authorities deciding which women deserved abortion.

Abortion reformers presented this patronizing position as a reasonable compromise between absolute abortion prohibition and outright repeal. The tactic had broad appeal with politicians and with voters. As much was apparent in Washington State, which saw a successful referendum campaign for abortion reform take place in November 1970. There, the abortion rights campaign emphasized that their program was “not abortion on demand” and underscored that “the medical profession [would] deal responsibly with women in crisis.” At a moment when 92% of physicians in the country were male, reformers made abortion reform palatable by maintaining “responsible” male medical authority. The implication was that these physicians would ensure that women’s access to abortion would remain limited to the deserving few.

This emphasis by reformers on continued male medical authority over women’s reproductive lives was also attractive to the very Protestant denominations that would later join the anti-abortion religious coalition after Roe.

During the early 1970s, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Southern Baptist Convention, and Seventh Day Adventists, along with other groups, rejected “abortion on demand” while supporting “therapeutic abortion based on approved medical indications.” As long as male medical authority over women’s reproduction remained, these groups endorsed abortion reform. This paternalistic perspective on abortion would eventually unite conservative Protestants and anti-choice Catholics.

As women began to take a more prominent role in the abortion repeal movement, they emphasized the feminist perspective that abortion reform was designed by men to keep women as submissive subjects. The feminist push for reproductive freedom became more visible, with large-scale protests and marches advocating for abortion on demand alongside other women’s rights issues.

Opponents of abortion, primarily led by the Catholic Church, began to associate abortion on demand with mass murder and other moral horrors, intensifying their efforts against expanded abortion access. Politicians like Richard Nixon aligned themselves with the anti-abortion movement to appeal to socially conservative Catholic voters, contributing to the transformation of Republican politics.

The Supreme Court’s rulings in Roe v Wade and Doe v Bolton solidified many demands of the repeal movement, making abortion more accessible and frequent. The victory of abortion repeal created a divide within religious constituencies, driving conservative Protestants to join the anti-abortion movement previously dominated by Catholics.

Over time, the negative associations of abortion on demand with gender hierarchies became entrenched in Republican policies, shaping politics for decades. Some Democratic politicians attempted to find a middle ground between reproductive freedom and outright abortion bans by using phrases like “safe, legal, and rare.”

Today, the meaning of “abortion on demand” is once again uncertain as laws surrounding abortion are rapidly changing, with some states enacting total bans or severe restrictions. The ongoing debate over abortion rights continues to be a contentious issue in American politics. Some conservative states only allow abortions in cases of rape or incest, making it challenging for women facing tragic circumstances to access the procedure locally. The recent Supreme Court case, Dobbs, may have threatened Roe v. Wade, but the fight for abortion rights and women’s equality continues. Within the abortion rights movement, there are ongoing debates about who deserves access to abortion and whether women should have the autonomy to make their own reproductive choices. Despite these internal discussions, the threat of religious movements advocating for abortion bans lingers, indicating that women’s reproductive freedom remains a contentious issue. Gillian Frank, a historian specializing in religion and sexuality, co-hosts the podcast Sexing History and is working on a book titled A Sacred Choice: Liberal Religion and the Struggle for Abortion Before Roe v Wade, to be published by the University of North Carolina Press. Please rewrite this sentence.

Source link