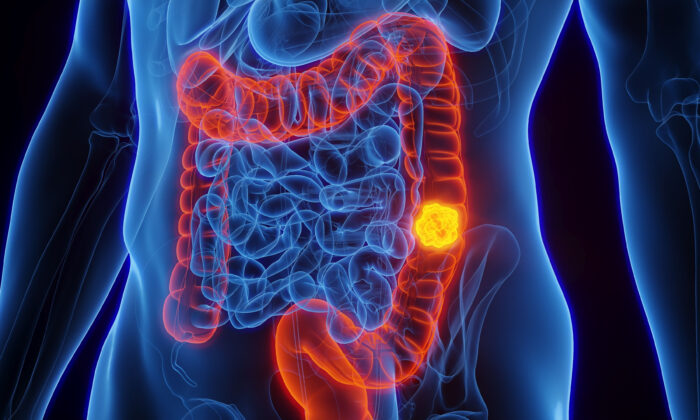

New findings related to microbes in colon cancer have the potential to revolutionize screening methods and pave the way for microbial-based therapies targeted at tumors.

A recent study has revealed that a common oral bacterium associated with an aggressive form of colorectal cancer may be driving the growth of tumors.

Importance of the Findings

Fusobacterium nucleatum is of particular interest because patients with detectable levels of this bacterium tend to have a poorer prognosis and survival rate, as explained by Susan Bullman, a cancer microbiome researcher at Fred Hutch and co-author of the study, in a press release.

“Now we’re discovering that a specific subtype of this microbe is responsible for tumor growth,” she stated. “This suggests that therapeutics and screening methods targeting this subgroup within the microbiota could benefit individuals at higher risk of aggressive colorectal cancer.”

The specific subtype of Fusobacterium, known as Fna C2, was found in half of the tumors examined in the study. It was also present in higher concentrations in stool samples from 627 colorectal cancer patients compared to 619 healthy individuals in a separate analysis included in the study.

Fna C2 was one of two distinct lineages of Fusobacterium nucleatum identified in the colorectal tumors, demonstrating 195 genetic variances from the other clade, referred to as Fna C1. Characteristics of Fna C2 suggest its ability to withstand stomach acid and thrive in the colon.

Potential for Prevention, Screening, and Treatment

“We have identified the specific bacterial lineage associated with colorectal cancer, and this knowledge is crucial for developing effective preventive and therapeutic strategies,” stated Christopher D. Johnston, a molecular microbiologist at Fred Hutch and co-corresponding author, in the press release.

However, the development of such tools may require additional research before implementation, according to Dr. Marty Makary, a cancer surgeon at Johns Hopkins, who spoke to The Epoch Times.

“One might assume that preventing colon cancer could be as straightforward as eliminating that particular strain of Fusobacterium from the gut. However, the gut exists in a delicate balance, and altering it could lead to unforeseen issues,” he cautioned.

Disruption of Gut Microbiota

The gut microbiota comprises trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms. While past focus has been on pathogenic microbes and antibiotics that can eradicate the entire community, recent studies are revealing a connection between the overall microbiome composition and various diseases.

“Our actions towards the microbiome are not fully understood,” noted Dr. Makary, a bestselling author whose latest book is “Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health.” “The use of antibiotics and other interventions may promote the growth of inflammatory bacteria, which has been implicated in cancer development.

“There are underlying factors at play. Unfortunately, the medical field has overlooked the significance of microbiome research and underfunded its role in cancer and chronic diseases.”

Impact of Antibiotics

In fact, it is possible that modern medical interventions have triggered the initial disruption. Dr. Makary highlighted research indicating a correlation between antibiotic use—known to eliminate beneficial microbes in the gut microbiome—and the presence of colon polyps, which could precede colon cancer.

Lessons Learned from History

While the recent study highlights a potential link between the microbiome and colorectal cancer, Dr. Makary emphasized the possibility of multiple microbes being involved. He stressed the importance of recognizing medical biases and embracing an open-minded approach to studying the microbiome comprehensively.

“Our understanding of the microbiome is just scratching the surface,” he remarked. “As long as we focus solely on chemotherapy without investigating the root causes of cancer, we will overlook the microbiome’s role in cancer and chronic diseases.”

The potential microbial connection to colon cancer explored in this study mirrors the discovery that H. pylori can induce stomach ulcers, Dr. Makary pointed out.

Heliobacter pylori, a prevalent bacterium found in most individuals, can harm stomach and small intestine tissues, triggering a hyperinflammatory state that may lead to peptic ulcers in the upper digestive tract.

“Initially, the medical community dismissed the notion proposed by researchers and attributed the issue to stress, rather than a single bacterium in the microbiome. However, subsequent research confirmed a direct correlation,” Dr. Makary recalled. “By acknowledging our research blind spots and applying the same rigorous methodology used in pharmaceutical studies to microbiome research, we can make significant strides in understanding and addressing the escalating rates of cancer among young people.”