Commentary

A second “D” has been added to “DEI.” The pervasive diversity, equity, and inclusion trio has been repackaged as “EDID”: equity, diversity, inclusion, and decolonization. Like DEI, decolonization holds that society is systemically divided between a class of oppressors/exploiters and various victimized/oppressed minorities defined by their (racial, sexual, etc.) identities. And while the designated victim groups are fluid and shifting, the oppressors invariably fall into one category: “privileged” “white” “European” “settlers.”

Now firmly nested in Canada, decolonization is by far the most dangerous of this ideological quartet. If we’re not careful, it will lead to serious bloodshed. This first installment of my three-part series focuses on decolonization’s origins.

Though not a brand-new idea, the ideology was able to break out of its original confines in African colonies and European study halls as proponents came up with new variations on the concept. North American academics began to claim that “decolonizing” need not involve actual colonized geographical spaces nor even political units at all, but could apply to organizations, companies, professions, academic disciplines, and even scientific fields.

Closely linked to the rest of DEI as it may be, decolonization is more than a mere add-on. It was actually the first and worst of the bunch, and its current revival also makes it the final: an explicit call to arms, a means not just to gain power within existing social and political structures but to tear those very structures down.

Where did this madness begin? In Europe, of course. Central among decolonization’s small coterie of founding theorists was Caribbean-French psychiatrist Frantz Fanon. Born and raised on France’s island-colony of Martinique, Fanon fought for Charles de Gaulle’s Free French Army in the Second World War, experienced racism as a black soldier in Europe, then studied in France, earning degrees in medicine and psychiatry.

For Fanon, decolonization was as much a psychological as a political process. It was to become a program not merely of political decoupling but of complete disorder—a total, unstructured upheaval with violence a central feature. As he wrote, “The practice of violence binds [the people] together as a whole, since each individual forms a violent link in the great chain, a part of the great organism of violence which has surged upward in reaction to the settler’s violence in the beginning.”

Coming out as it did after numerous former colonies and European-ruled mandates had achieved independence peacefully—India, Egypt, and Oman from Britain, Syria from France, to name a few—while others fought wars but then made peace and maintained close ties with their former colonizers, “The Wretched of the Earth” can be regarded as one-sided and tendentious.

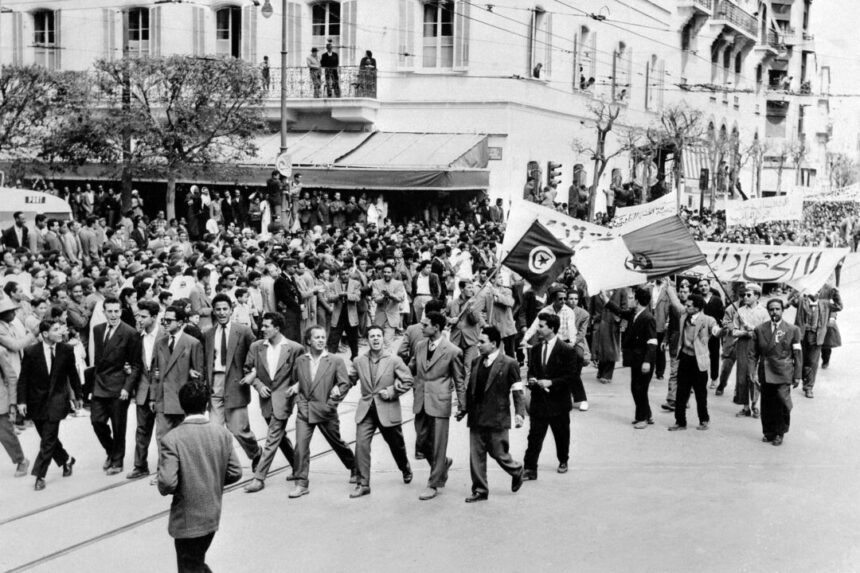

Even worse, it poured gasoline onto the political bonfires burning throughout Africa and other regions, including France’s war with the Algerian National Liberation Front, which would kill upwards of 500,000 people. Fanon found an all-too-willing audience; the first rulers of newly independent Algeria immediately massacred 100,000–300,000 Algerians who had worked with the French.

Fanon inspired guerrilla movements across sub-Saharan Africa, notably in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. Thomas Sankara, who installed himself as autocrat of the already-independent Republic of Upper Volta in a 1983 coup d’état, had formally studied Fanon’s work. Fanon’s echoes sound in Sankara’s speeches, like his declaration of the “necessity of madness for fundamental transformation.”

Fanon also influenced Cuban communist revolutionaries like Che Guevara and the U.S. Black Panthers in the late ’60s or early ’70s. Fanon’s “by any means necessary” approach was also espoused by Malcolm X and, more recently, embraced in movements like BLM, Antifa, and today’s pro-Hamas organizations.

The Fanon formula proved intoxicating to leftist intellectuals in European countries, who used it as another weapon in their long campaign to delegitimize Western civilization, in turn accelerating the erosion of self-confidence among Western elites.

And, as improbable as it sounds, decolonization even gained a foothold in the former colony of Canada, which had peacefully gained its independence more than a century earlier—a subject explored in Part 2 of this series.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

Please rephrase

Source link