WASHINGTON—The Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy near our Milky Way, is visible to the naked eye from Earth’s southern hemisphere. Named after Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who observed it five centuries ago, new research is shedding light on the composition of this galactic neighbor.

A recent study analyzing the trajectories of nine fast-moving stars at the edges of the Milky Way provides compelling evidence for the presence of a supermassive black hole within the Large Magellanic Cloud. While most galaxies are believed to host such black holes at their cores, this discovery marks the first evidence of one within the Large Magellanic Cloud.

Researchers suggest that the stars’ trajectories indicate they were ejected from the Large Magellanic Cloud following a violent encounter with the black hole. Black holes are incredibly dense objects with gravitational forces so strong that even light cannot escape.

Situated approximately 160,000 light-years from Earth, the Large Magellanic Cloud is one of the closest galaxies to the Milky Way. This makes the newly identified supermassive black hole the closest to us, apart from Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), located at the heart of the Milky Way and about 26,000 light-years away. A light-year represents the distance light travels in a year, equivalent to 5.9 trillion miles.

Although the Milky Way is much larger than the Large Magellanic Cloud, Sgr A* is significantly more massive than the newly discovered black hole, which is among the least massive supermassive black holes known. Sgr A* has a mass approximately 4 million times greater than that of the sun, while the newly identified black hole has a mass about 600,000 times greater than the sun’s.

Comparatively, some supermassive black holes in other large galaxies dwarf Sgr A*, with one in Messier 87 boasting a mass 6.5 billion times greater than that of the sun. Sgr A* and the black hole in Messier 87 are the only two black holes that astronomers have imaged.

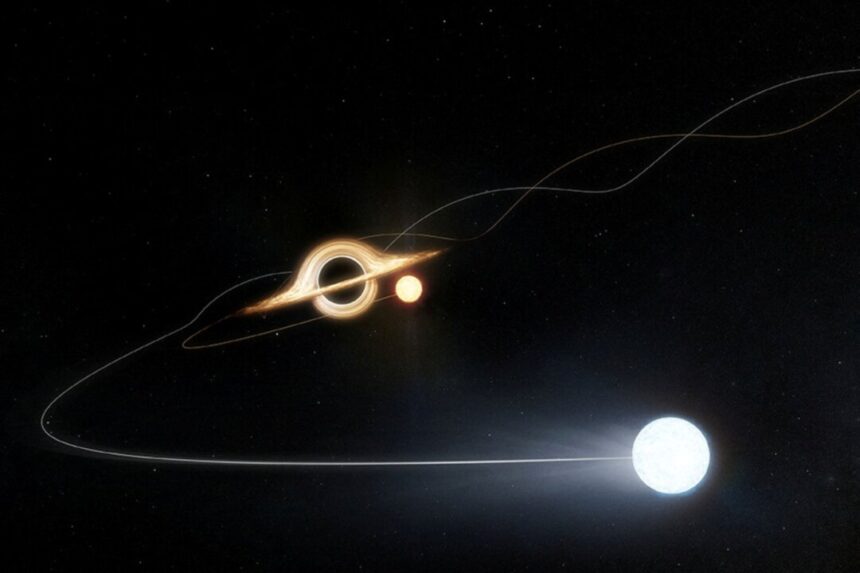

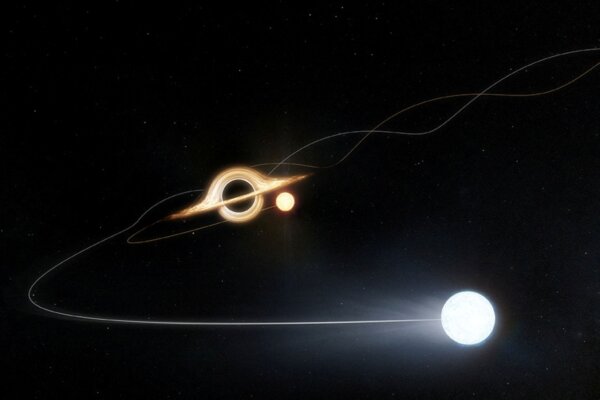

The study focused on hypervelocity stars, which form when a binary star system—two stars gravitationally bound to each other—approaches a supermassive black hole too closely.

According to Jesse Han, a doctoral student in astrophysics at Harvard University and lead author of the study, “The intense gravitational forces tear the pair apart. One star is captured into a tight orbit around the black hole, while the other is flung outward at extreme velocities—often exceeding thousands of kilometers per second—becoming a hypervelocity star.”

While the sun travels through space at around 450,000 miles per hour, hypervelocity stars move at speeds several times faster.

Utilizing data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia space observatory, which has meticulously tracked over a billion stars in our galaxy, the researchers identified 21 hypervelocity stars in the Milky Way. Of these, the origins of 16 have been confidently determined, with seven tracing back to Sgr A* and nine to the Large Magellanic Cloud.

According to Han, “The only plausible explanation is that the Large Magellanic Cloud houses a supermassive black hole in its center, similar to Sgr A* in our galaxy.”

Caltech astronomer and study co-author Kareem El-Badry noted, “The Large Magellanic Cloud, given its mass and structure, is expected to have a supermassive black hole of this mass. We simply needed to find the evidence for it.”

Until now, the closest known supermassive black hole beyond the Milky Way was located in the Andromeda galaxy, approximately 2.5 million light-years away from Earth, making it the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way.

El-Badry added, “The Large Magellanic Cloud is one of the most extensively studied galaxies, yet the existence of this supermassive black hole was only inferred indirectly by tracing the origins of fast-moving stars. We still have work to do to precisely pinpoint the black hole’s location.”

By Will Dunham