I recently presented at the Louisville Federalist Society Chapter on presidential immunity. Following the discussion, I had the privilege of exploring the Library’s special collections, which house papers from Justice Louis Brandeis and Justice John Marshall Harlan I. I have previously engaged with Justice Harlan’s papers at the Library of Congress and even co-authored a paper transcribing his constitutional law lecture notes with Brian Frye and Michael McCloskey. I continue to draw inspiration from Harlan’s insights in my teachings, such as emphasizing the importance of the Supremacy Clause in the Constitution. I have also had the pleasure of corresponding with Peter Scott Campbell, a librarian at Louisville, who graciously provided a tour of the collection.

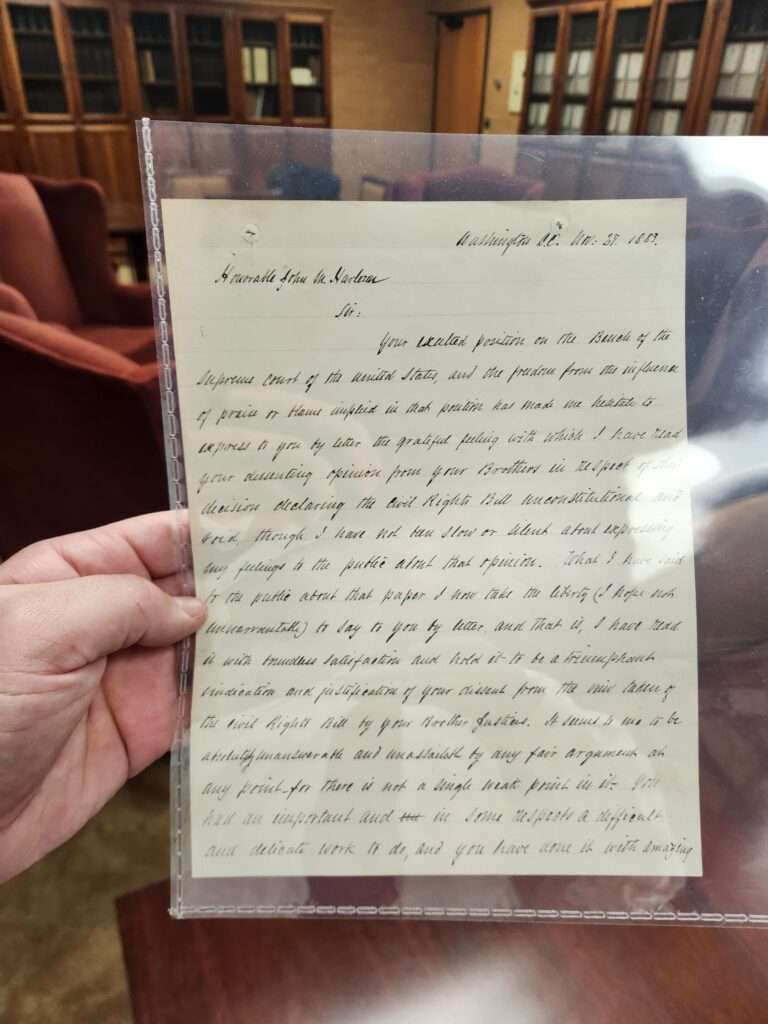

Among the remarkable pieces I encountered was a letter from Frederick Douglass to Justice Harlan following the Civil Rights Cases of 1883. Douglass’s eloquent words praising Harlan’s dissent underscore the significance of his stance. I firmly believe Harlan’s perspective in the Civil Rights Cases was correct and could have reshaped subsequent legal outcomes. Douglass’s inclusion of an article from The American Reformer newspaper further highlights the impact of Harlan’s dissent.

[Harlan’s dissent] seems to me to be absolutely unanswerable and unassailable by any fair argument at any point for there is not a single weak point in it. You had an important and in some respects a difficult and delicate work to do, and you have done it with amazing ability skill and effect. . . . I have nothing bitter to say of your Brothers on the Supreme Bench, though I am amazed and distressed by what they have done. How they could at this day and in view of the past commit themselves and the country to such a surrender of National dignity and duty, I am unable to explain. I have read what they have said, and find no solid ground in it. Superficial and [???], smooth and logical within the narrow circumference beyond which they do not venture, that is all.

Douglass’s insights on the Civil Rights Act of 1875 and Harlan’s dissent resonate profoundly, shedding light on the broader constitutional implications. His articulation of constitutional principles, particularly regarding the Equal Protection Clause, is both insightful and relevant to contemporary legal discussions. Additionally, Douglass’s acknowledgment of Justice Curtis’s dissent in the Dred Scott case further underscores the enduring impact of judicial dissent in shaping legal history.

Curtis resigned from the Supreme Court shortly after Chief Justice Taney’s decision, a fact not widely known. Douglass held Curtis in high esteem, and Harlan joined that esteemed group. It is unlikely that Justice Story, the author of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, would be included in that group.

Douglass uses the phrase “grapples with substance rather than shadow,” a phrase also used by Chief Justice Roberts in the Trump immunity decision.

Douglass’s praise for Justice Harlan’s moral courage, especially coming from a slave state, is noteworthy. Harlan’s principled stance during the reconstruction era is commendable, and his actions demonstrate great fidelity, skill, and effect.

The concept of judicial courage, discussed at length in various sources, including political science departments, is not new. Douglass’s emphasis on the importance of courage in judges’ decisions dates back to earlier times.

Courage, as Douglass argued, means standing alone for one’s principles and being willing to dissent. Lone dissents, like those issued by Justice Thomas and Justice Alito, require courage. Justice Scalia’s Morrison dissent is another example of this courage.

In a related point, archival documents from Justice Brennan’s papers show his appreciation for a Supreme Court advocate who defended the Court. These documents will be shared at the appropriate time. Please rewrite the text for me.

Source link