Approximately 5,000 years ago, the population of northern Europe saw a significant decline, leading to the devastation of Stone Age farming communities in the area. The cause of this event, known as the Neolithic decline, has been a topic of discussion among researchers.

New findings based on DNA extracted from human remains found in ancient burial sites in Scandinavia—specifically from seven individuals in Falbygden, Sweden, one from coastal Sweden near Gothenburg, and one from Denmark—suggest that disease, particularly the plague, might have been responsible for the Neolithic decline.

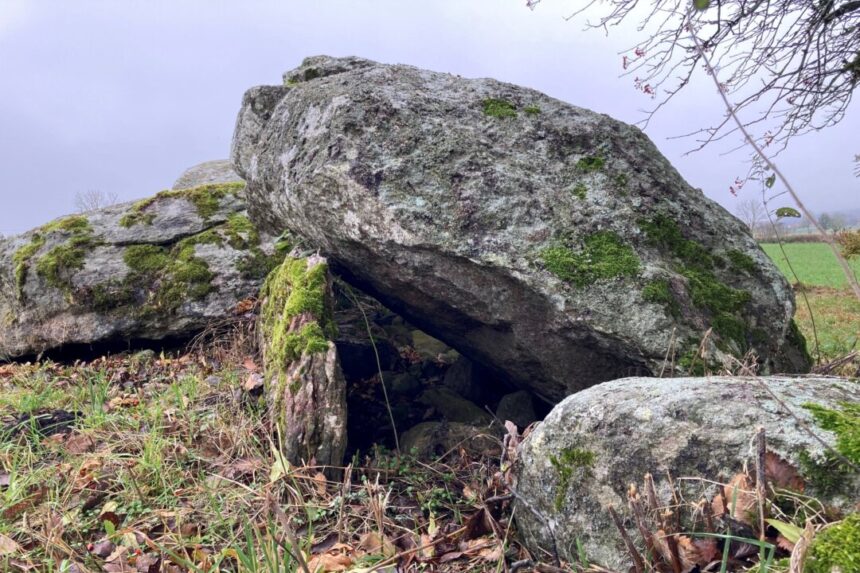

The human remains were discovered in megalithic tombs known as passage graves, constructed from large stones.

A total of 108 individuals—62 males, 45 females, and one undetermined—were analyzed, with 18 of them (17 percent) found to have been infected with the plague at the time of their death.

Researchers were able to trace the family lineage of 38 individuals from Falbygden over six generations, spanning approximately 120 years. Among them, 12 individuals (32 percent) were infected with the plague. Genomic analysis revealed that their community experienced three distinct waves of an early form of the plague.

By reconstructing the full genomes of different strains of the plague-causing bacterium Yersinia pestis responsible for these outbreaks, researchers identified the last wave as potentially more virulent than the others. They also found characteristics indicating that the disease could have spread from person to person, leading to an epidemic.

“We discovered that the Neolithic plague is an ancestor to all later forms of the plague,” stated lead author Frederik Seersholm, a geneticist from the University of Copenhagen, whose research was published in the journal Nature.

A later variant of the same pathogen caused the Justinian Plague in the 6th century AD and the Black Death in the 14th century, which devastated Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Due to the early nature of the strains during the Neolithic decline, the symptoms caused by the plague may have been different from those observed in later epidemics.

The study indicated a high prevalence of the plague in the examined region.

“The significant presence of the plague suggests that plague outbreaks played a crucial role in the Neolithic decline in this area,” noted co-author Martin Sikora, a geneticist from the University of Copenhagen.

“Indeed, it is possible that the decline seen in other parts of Europe was also influenced by the plague. We already have evidence of the plague in other megalithic sites across Northern Europe. Given its prevalence in Scandinavia, we anticipate a similar pattern when studying these other megaliths in detail,” added Sikora.

The Neolithic period, characterized by the adoption of farming and animal domestication, saw a population crash in Northern Europe from around 3300 BC to 2900 BC. By this time, advanced civilizations had already emerged in regions like Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The populations of Scandinavia and Northwestern Europe eventually vanished completely, to be later replaced by the Yamnaya people who migrated from the steppe regions of present-day Ukraine. These individuals are the ancestors of modern Northern Europeans.

“Various scenarios have been proposed to explain the Neolithic decline, including warfare, competition with steppe-related populations, agricultural crises, and diseases such as the plague,” Seersholm explained. “The challenge was the lack of sufficient plague genomes and uncertainty regarding the disease’s ability to spread among humans.”

The DNA evidence also shed light on the social structure of these communities, revealing that men often had children with multiple women, while women appeared to be monogamous and were brought in from neighboring communities.

“The presence of multiple reproductive partners could indicate several wives or the practice of men finding new partners after becoming widowers. The women, however, seemed to adhere to monogamy,” Seersholm elaborated.

By Will Dunham