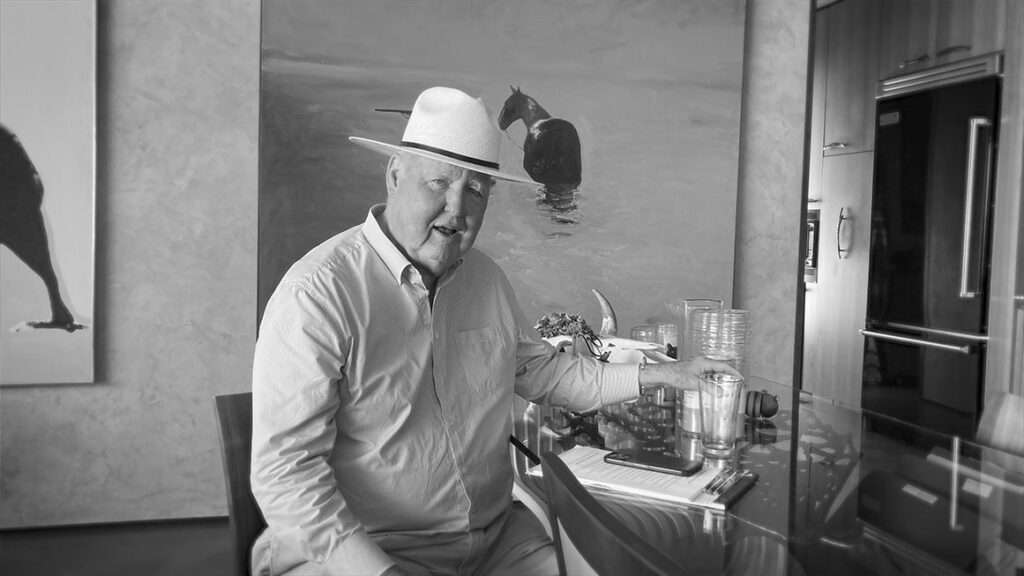

“I’m having the lawyers inquire as to whether or not I can bring a library with me to prison,” Michael Lacey said with resignation. The Backpage co-founder and former alt-weekly magnate was standing in the library of his labyrinthine Paradise Valley, Arizona, home. The room abuts one of Lacey’s two home offices, each teeming with books, family photos, journalism awards, and file folders—a mix of case files and past work he’s been combing through as he works on a book proposal.

It was March 2024, and Lacey was still holding out hope of avoiding federal prison. But prosecutors were eager to send him there, and Lacey recognized that may well be his fate.

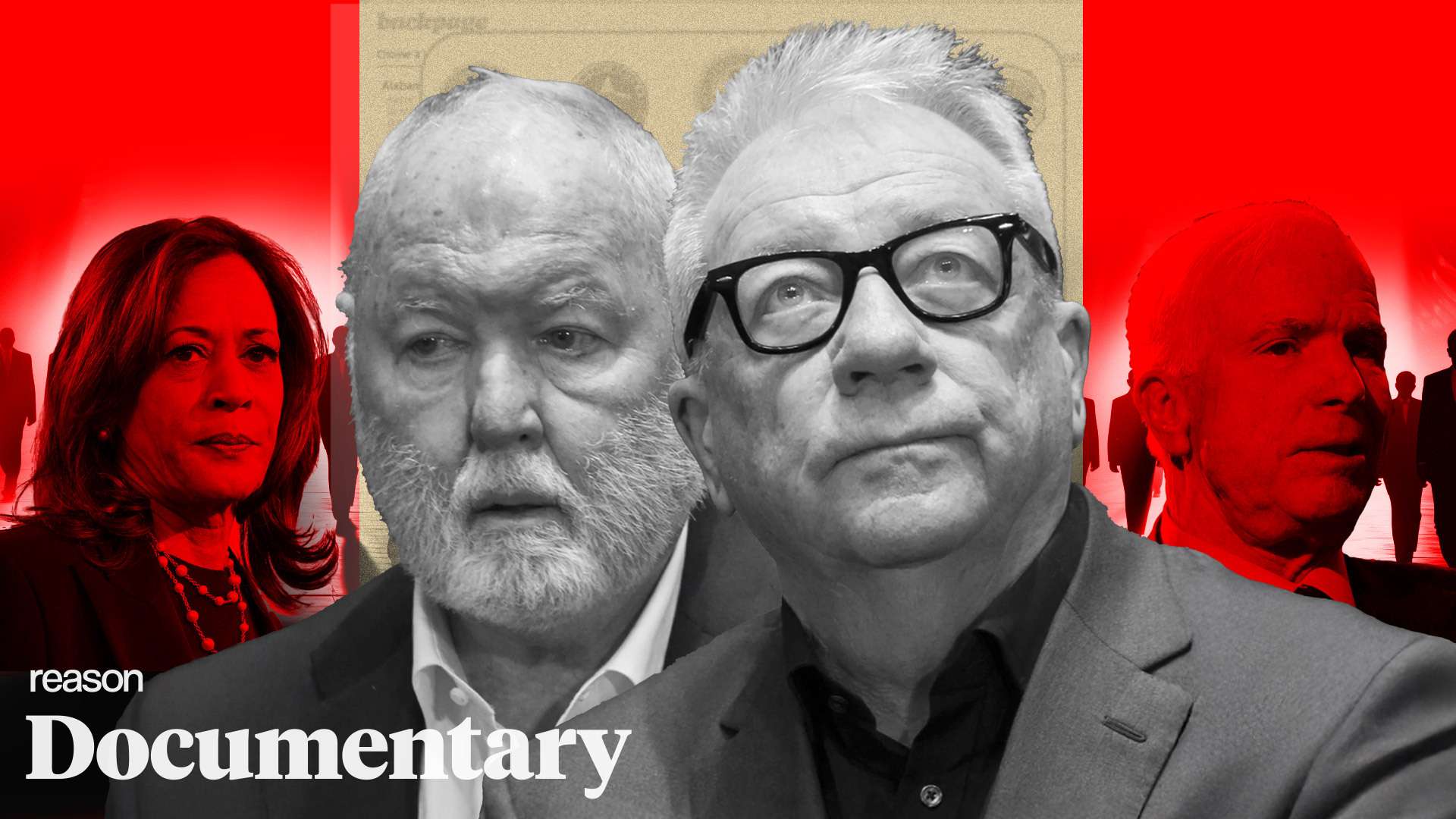

I was there with a Reason video crew, interviewing Lacey for a documentary. This was my second visit to Lacey’s home. The first, in 2018, was not long after the feds raided the place, and the vibe was different then. Lacey and his longtime friend and business partner James Larkin were pissed but not dejected. They cracked jokes about their enemies—folks such as Sen. John McCain (R–Ariz.) and former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio. They told elaborate stories about the heyday of their alt-weekly empire, finishing each other’s sentences. They broke out wine from Larkin’s vineyard and vowed they would fight this to the end.

Larkin committed suicide a week before the pair’s second federal trial was scheduled to start in August 2023.

In my second visit, Lacey was still cracking jokes and telling stories. But no one was there to finish his sentences, to remind him of the name of some official they angered once upon a time, to laugh with him about the wild office parties they threw in the 1970s, to try to rein him in (not always successfully) when his language got a little too colorful. “I still catch myself before I’ve had coffee, saying ‘Ah, I’ve got to send this to Jim,’ OK? I’ll see something and it’s like: ‘Oh, fuck. No sending anything to Jim.'”

In September, Lacey turned himself over to the U.S. Marshals—no library in tow, unsure even where he’d be imprisoned. Prosecutors recommended a 20-year sentence for the 76-year-old Lacey. U.S. District Judge Diane Humetewa instead sentenced him to five years plus a $3 million fine.

Lacey’s path from journalist to felon is at once unique—a product of particular times, temperaments, technological changes, and moral panics—and all too familiar. It’s a story of how far government agents will go to punish people who defy them, and a playbook for authorities intent on wresting more control over online speech of all sorts.

How It Started

Lacey and Larkin were no strangers to First Amendment conflicts when the Backpage prosecution started. Their friendship and business partnership began as part of the team running a scrappy anti-war student paper called the Arizona Times that launched in 1970. It would grow into the Phoenix New Times, a thriving weekly unafraid to skewer Arizona power players, including Arpaio, McCain and wife Cindy, and many others.

In the 1980s and 1990s, their portfolio grew to include alternative weeklies in more than a dozen cities, including the iconic Village Voice in Greenwich Village. Lacey mainly handled editorial and Larkin handled the business end of things.

Both fought in court again and again, defending their First Amendment right to distribute, write, and—this is the part that finally brought them to ruin—run ads as they saw fit. New Times was even convicted in 1971for running an abortion services ad, but it fought the case to Arizona’s Court of Appeals, which ruled in the paper’s favor and struck down the state’s law against advertising abortions or birth control.

In 2004, Lacey and Larkin launched the website Backpage as an extension of the classified ads that had always run in the back of their newspapers (and most other newspapers). Backpage.com had all the sections you would find in its print counterparts, including apartments for rent, job openings, and personals and adult services ads, separated by city.

At first, nobody paid much attention to the site. When attorneys general declared war on adult services ads online in the late 2000s, the similar but better-known Craigslist was the platform in their crosshairs.

Though newspapers had for decades published ads for escorts, phone sex lines, and other forms of legal sex work, Craigslist’s online facilitation of these ads coincided with two burgeoning moral panics. The first concerned the rise of user-generated content—platforms such as Craigslist and early social media entities that allowed speech to be published without traditional gatekeepers.

The second panic: sex trafficking. A coalition of Christian activists and radical feminists had been teaming up to push the idea that levels of forced and underage prostitution were suddenly reaching epidemic proportions. To support this narrative, they tended to conflate all prostitution or even any sort of sex work with coerced sex trafficking.

Becoming a Target

“Sex trafficking is usually the way it was framed, even when it was consensual sex work,” says Techdirt founder and editor Mike Masnick, who has been covering tech policy since the 1990s. “Finally Craigslist was like, ‘forget it.'” The platform shuttered its adult ad section. “And then you have the same A.G.s complaining about Backpage. And it’s like, ‘Oh, OK, that’s where everybody went.'”

In 2012, then–California Attorney General Kamala Harris said: “Backpage.com needs to shut itself down when it has created as its business model the profiting off the selling of human beings and the purchase of human beings….Good businesses, such as Craigslist, understood how it could be abused and mishandled and they shut that aspect of their business model down.”

Harris was far from alone in making these kinds of statements. For years, politicians on both sides of the aisle perpetuated the false narrative that Backpage facilitated human trafficking, including underage girls. However, this was not the case. The company had strict policies against illegal ads, reported suspicious activity to authorities, and collaborated with law enforcement to combat sexual exploitation.

Despite prosecutors arguing that some ads were thinly veiled solicitations for prostitution, Backpage maintained that as long as the posts did not explicitly offer illegal services, they were legal. Many lawyers agreed that the business was operating within the bounds of the law.

Backpage had established relationships with law enforcement agencies nationwide, with CEO Carl Ferrer even testifying against alleged traffickers in court. Federal prosecutors acknowledged the company’s cooperation and efforts to prevent criminal activity, but these positive assessments were not admitted in court.

The company faced legal challenges and political pressure, with critics accusing it of being a hub for sex trafficking. Lacey and Larkin believed that this backlash was fueled by personal vendettas from politicians they had criticized in their publications. Additionally, the heightened concern over sex trafficking made it difficult for defenders of free speech to support Backpage.

Despite facing lawsuits, bullying tactics, and criminal charges, Backpage maintained that it was operating lawfully under the Communications Decency Act. The legal battles and negative publicity ultimately led to the downfall of the platform. Despite this, the Harris presidential campaign still had a speaker at the Democratic National Convention mention the criminal charges favorably.

Section 230 of the CDA protects interactive computer services and their users from state criminal charges and civil lawsuits related to content created by third parties. This means that platforms like Facebook are not held liable for threats posted by users, and individuals who share content are not responsible for the content itself. Critics of Section 230 argue that it shields tech companies from accountability for criminal activities conducted on their platforms by shifting blame to the perpetrators.

In 2018, Congress passed FOSTA, weakening Section 230 in response to allegations that websites like Backpage were facilitating sex trafficking. However, the timing of this legislation raised questions as Backpage had already been shut down and charges filed before the law was enacted.

The legal battle surrounding Backpage involved accusations of facilitating prostitution, money laundering, and conspiracy. Prosecutors attempted to portray the case as a sex trafficking issue, despite the charges being different. The defense faced challenges in presenting their case, as the government sought to limit their ability to reference the First Amendment, Section 230, or legal advice received by the site over the years. The state requested restrictions on references to the 2021 mistrial, Lacey and Larkin’s journalism career, and the defendant’s families. Judge Humetewa partially rejected the ban on First Amendment references but approved most other limitations on Lacey and colleagues’ defense. Larkin tragically took his own life a week before the trial. Lacey expressed shock and grief, highlighting Larkin’s legal advice and the government’s role in his death.

The shutdown of Backpage and FOSTA’s passage did not improve safety. Online sex work ads shifted to other platforms, complicating law enforcement efforts. Sex workers lost independence and faced increased risk post-Backpage. A study in the journal Social Sciences highlighted negative effects on sex workers due to online platform restrictions.

Politicians, like Sen. Marsha Blackburn, have targeted social media platforms under the guise of combating sex trafficking. This approach jeopardizes privacy and free speech rights. The tactics used against Backpage are now being used against other tech companies, with harmful consequences.

Lacey faced ongoing legal battles even after Larkin’s death. He emphasized his lack of involvement with Backpage, a defense tactic he avoided while Larkin was still alive. The trial continued with mixed outcomes for the remaining defendants. Vaught’s attorney, Joy Bertrand, expressed to reporters that her client should never have been involved in this case. She stated that Vaught was charged and pressured to cooperate with the government, but she had the courage to refuse. Former executives Jed Brunst and Scott Spear were acquitted on some counts and convicted on others. Michael Lacey was found guilty of international concealment money laundering, stemming from parking proceeds from the sale of Backpage in an offshore trust for his sons. His lawyers argued that there was no intent to conceal, but rather an intent to disclose. While Lacey was found guilty of some charges, a mistrial was declared on others. Judge Humetewa dismissed 50 counts against Lacey due to insufficient evidence. However, there are still 34 remaining counts on which prosecutors could retry Lacey. Despite already facing a five-year prison sentence, prosecutors have indicated they may bring Lacey to trial again. This highlights the power of government prosecution to potentially ruin individuals, as emphasized by a statement from Larkin in 2023. Please rewrite this sentence.

Source link