Sabra Brucker works as an executive assistant. Her husband, Dagan, is a fifth-generation farmer in Cropsey, Illinois, about 100 miles south of Chicago.

After many years of infertility and miscarriages, they finally became the parents of four young children: Addison, born in 2017; Andi, born in 2019; and twins Aiden and Arie, born prematurely in March 2021.

The Brucker family had never previously endured a run-in with child protective services. A series of medical complications involving the younger twin, Aiden, suddenly changed that. After the parents sought care for their sick child, they were falsely accused of breaking Aiden’s ribs and subjected to months of humiliating inequity. And when that was over, the authorities refused to disclose the identity of the actual perpetrator.

“I never thought that this was even humanly possible,” says Sabra. “To be honest, I was probably naive.”

When Aiden was 5 months old, the Bruckers discovered he had genetic intestinal malrotation—the same condition that had required emergency surgery to save his older sister Addison’s life back when she too was 5 months old.

On August 9, 2021, the Bruckers took Aiden to the OSF Children’s Hospital Emergency Room in Peoria, Illinois. He was experiencing intense stomach pain and vomiting, just as his older sister had. Genetic intestinal malrotation can be a life-threatening condition, and it requires immediate, emergency intervention.

Aiden’s condition, though serious, was not as immediately life-threatening as Addison’s had been. He was given ultrasounds and X-rays for his upper GI track, abdomen, and chest. His intestinal reversal was visualized, but no skeletal concerns were noted. Nevertheless, he was held in the hospital for observation, and subjected to daily, repeated abdominal ultrasounds and chest and abdominal X-rays.

On the fourth day of his stay at the hospital, seven rib fractures became visible on the X-rays. These were all new, non-calcified fractures that had not appeared on earlier X-rays. Rib fractures are viewed by medical profession as evidence of possible abuse.

The Bruckers immediately suspected that the fractures had occurred during the hospital stay itself, possibly due to the extensive handling and exams Aiden had endured. The lack of any signs of these injuries at admission certainly suggested that they had appeared during Aiden’s inpatient care. And yet as soon as the fractures were detected, a child abuse hotline call was placed to the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) naming the Bruckers as suspected abusers.

Sabra was in a meeting with her boss when she received the news.

“I immediately called my husband—he was at the hospital with Aiden—and I said, ‘What is going on?'” Sabra recalls. “I just remember the sheer confusion and fear in his voice.”

Sabra and Dagan were not quick to point fingers, but they did wonder if the hospital was aware of its own potential liability when it accused them of causing the fractures.

Following the call to the child abuse hotline, a state-contracted child abuse pediatrician, Channing Petrak, assumed the role of directing Aiden’s medical testing as a suspected child abuse victim. Petrak oversees child abuse cases under a subcontract her office holds with the DCFS for central Illinois. While not a hospital employee, she is viewed as the head of the hospital’s child abuse team. In that capacity, she was empowered to decide which tests Aiden needed in order to confirm or rule out abuse.

She was also immediately enlisted to discuss the case with DCFS and the police and to determine whether child abuse had occurred. If she believed it had, her role would include testifying against the parents in the event the case went to court.

Petrak was responsible for testing not just Aiden but the other Brucker children as well. While parents have the right to refuse medical procedures that are not required by a court order or emergency, the fear of CPS retribution looms large.

On multiple occasions, Sabra requested a meeting with Petrak and the OSF team to ensure the timeline of the injuries was clear. She felt it necessary that everyone understand the fractures had not been present on Aiden’s body upon admission, as shown by multiple X-ray examinations. Clarifying this, she thought, would allow her and Dagan to work alongside the hospital to identify their underlying cause.

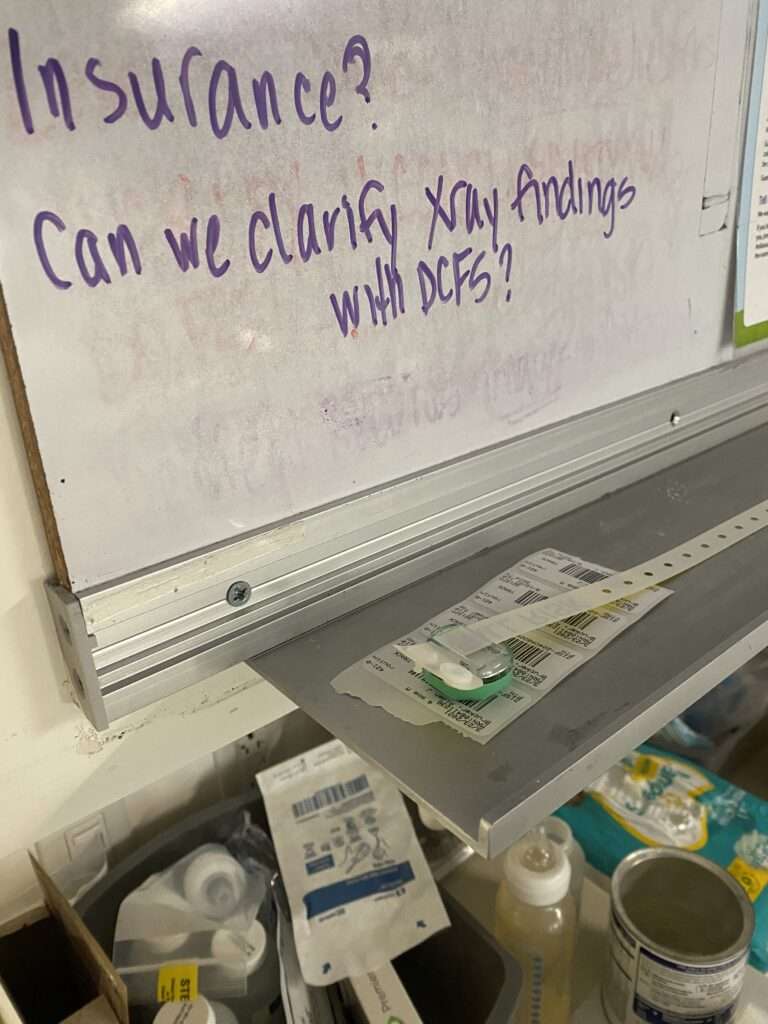

Sabra even wrote on the whiteboard the team used for notes: “Can we clarify Xray finds with DCFS?” and snapped a photo of it.

“I wanted a picture with a time stamp because no one would speak to me,” she says.

Meanwhile, Petrak pushed the family to authorize an MRI, which would require Aiden to fast for eight hours and then undergo general anesthesia and be intubated. As there was no suspicion of other injuries that would have made an MRI useful, the Bruckers tried to object.

In response, the hospital threatened the family with a court order that would require Aiden to remain in the hospital’s care pending a judicial order for the MRI. Since complying with the MRI demand seemed to be the only way to bring their son home quickly, Sabra comforted Aiden through the fast, and handed him over to the hospital’s staff—who sedated and intubated him, and proceeded with the MRI.

The other Brucker children—ages four, two and now six months—were also subjected to observation at their home. These included visual exams of their genitals.

The state even demanded that the 4-year-old daughter, Addison, submit to a forensic interrogator. This investigator reported that Addison was very “sweet” and “polite,” and no concerns were noted from her 2-hour interview.

Meanwhile, DCFS determined that the Bruckers could not take Aiden home by themselves upon his discharge. Instead, the agency demanded the family find someone else to take care of their four children. That person could do so at the Bruckers’ home, and Sabra and Dagan could live there—but they would not be allowed to be alone with their children at any time. If they not did find a caregiver to watch the kids 24/7, the children would be taken into foster care and placed with strangers.

Sabra’s parents, Don and Shari Boyd, lived 273 miles away. Thankfully, Shari was on hand to help out, even though she was in the middle of breast cancer treatment.

Diane Redleaf, a defense attorney who co-chairs the National Coalition to End Hidden Foster Care, says that the Bruckers’ experience is commonplace. Efforts are underway to secure reforms that would allow families like the Bruckers to have some recourse when they are threatened with having their kids taken away.

This arrangement for the children was supposed to last for just two to five days, but DCFS kept extending it. The caseworker even reminded grandma Shari that she couldn’t use the bathroom without taking the kids in with her. Sabra and Dagan’s nighttime feedings of their baby twins also had to be supervised by Shari.

The Bruckers wanted to object, but they felt they had no choice.

This led to odd situations, such as Dagan not being able to have his kids take turns riding the combine with him—their favorite fall activity. The combine had only two seats, so if one of the children rode along, Shari and the other three children would have to somehow ride along too, or the government’s plan would be violated.

As the weeks dragged on, the Bruckers worked to demonstrate that the abuse allegations against them were false. A University of Chicago pediatric orthopedic specialist, Christopher Sullivan, saw Aiden in his office and reviewed his radiology imaging and lab testing, formally concluding that the timing of the fractures’ first appearance made it impossible for them to have occurred prior to the hospital admission.

Sullivan also noticed that Aiden had very low Vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels, which made his bones extremely fragile. He concluded that the likeliest explanation for the fractures was routine handling at the hospital.

Despite this report—and many letters from the Bruckers’ pediatrician, family members, friends, and teachers—DCFS’s restrictions persisted.

Meanwhile, DCFS came to suspect that the Bruckers’ day care providers were Aiden’s possible abuse perpetrators. For that reason, DCFS told the Bruckers they could no longer send their kids there. Everyone who had ever been in contact with Aiden before his hospital stay had suddenly become a suspect.

Sabra requested that their two older children be allowed to keep going to their day care— with their familiar friends and routines—but the caseworker said no. The caseworker also continued to demand weekly check-ins with the Bruckers. Each time, she insisted on strip-searching the twins and commenting on natural bodily features, such as inverted nipples.

As the family languished, Sabra checked the mail one day and was shocked to find a bill from the hospital for over $60,000. Her private insurance provider had denied the payment for Aiden’s MRI as “medically unnecessary.” The Bruckers told the hospital’s billing department that they had not requested the MRI; it was done at the behest of Petrak. Soon after this, the Bruckers’ billing records disappeared from their file at the hospital.

Illinois gives DCFS 60 days to complete an investigation. Knowing this, the Brucker family decided on day 60 that they had had enough of the “voluntary safety plan.” They hired a lawyer with DCFS experience who confirmed their right to terminate the plan. He notified DCFS accordingly.

Three months later, in January 2022, a caseworker from a different DCFS regional office phoned Sabra to say their investigation file had been transferred. Since the children had not been seen by DCFS in several months, the new caseworker wanted to come observe them. The family declined this request. The new DCFS caseworker also informed Sabra that the Bruckers’ case file was completely empty of investigative notes.

In March, and again in October, 14 months after the case had begun, the Bruckers’ attorney submitted a complaint to the DCFS Inspector General. In November 2022, he received a response saying the inspector general was unable to investigate this complaint because the case was still open. The Bruckers couldn’t help but wonder whether DCFS was keep the status of the investigation ambiguous in order to avoid accountability.

Finally, in November 2023, the Bruckers received a letter from DCFS stating that the case was now closed and Dagan and Sabra were cleared of any wrongdoing. Curiously, the letter claimed that “someone” had been “substantiated” as Aiden’s abuser.

The Bruckers filed an inquiry as to who that person was. They were told they had no right to see these records.

Neither Petrak nor the hospital responded to a request for comment. A spokesperson for DCFS declared in a statement: “DCFS is mandated by Illinois statute to investigate any allegations of child abuse or neglect that is reported to our agency.”

In situations like the Bruckers’, which are far too numerous to be viewed

Source link