Commentary

After the Stewart-Howe debate, which took place over two days, Tupper, then 23 years old, was called out “to see a man threatened with tetanus,” also known as “lockjaw,” a severe disease of the nervous system caused by bacterial infection. Dr. Tupper rode 30 kilometres on horseback to see the sick man. Taking the bedside manner quite literally, he stayed by his patient all night, returning home on horseback the next day.

But Frances Tupper had already answered by messenger that her husband would attend as soon as he got home. Tupper promised Townshend that he “would go and return without stopping.”

Tupper set out “as soon as a fresh horse was harnessed.” He saw Colonel Armstrong, prescribed medicine, and immediately got back on his wagon and “turned my face homewards.” Stopping only to eat and barely able to keep awake at the reins, he got within 30 kilometres of home when another patient at Maccan, 15 kilometres south of Amherst, needed him. Arriving at the patient’s house, Tupper asked for tea to keep him awake. But while waiting for the kettle to boil he fell asleep in a chair and could not be awakened for four hours.

On another occasion he rode out 40 kilometres to attend to a Mrs. Livingston. The case was bad, and he took with him “amputating instruments” which meant a set of saws, knives, vise-grip, and choppers to remove a limb but no modern anesthesia (pioneered in England and America in the 1840s) or modern antiseptic (pioneered by Joseph Lister in 1867, the year of Confederation).

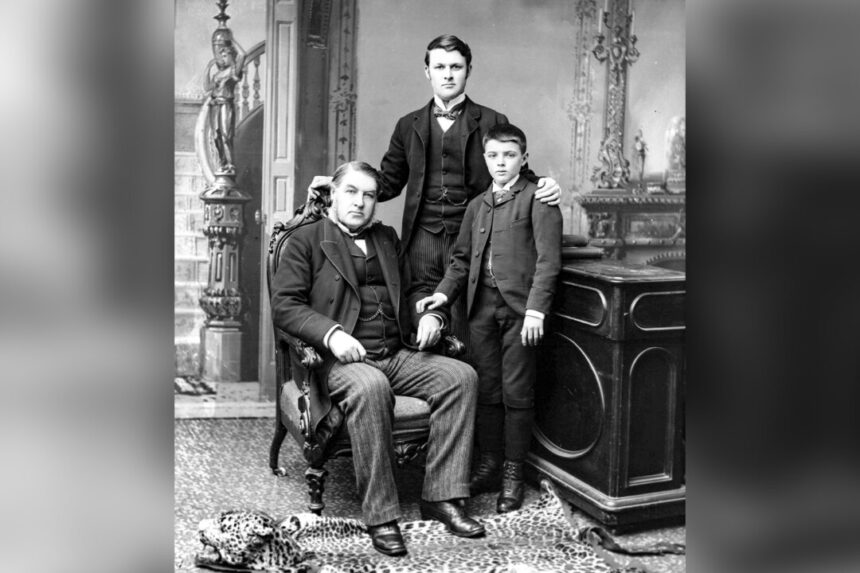

Sir Charles Tupper in 1865. Public Domain

The woman had “osteosarcoma of the femur,” Tupper later wrote, a large cancerous growth in the upper leg. She had shrunk to a skeletal figure, was in great pain, and had not slept for six weeks. When Tupper told Mrs. Livingston that he would have to amputate at the hip and that she might die during the operation, she said she would be better off either way: “If I was sure I could not live through the operation I would beg you to take my leg off.”

He asked a new doctor in Pugwash, eight kilometres away, to assist him in the operation the following morning. Tupper also enlisted a sailor (the profession most experienced in tying knots) and showed him “how to ligature an artery.” The initial cuts being made to the flesh and arteries, the younger doctor “compressed the femoral artery” while Tupper “made the anterior flap,” which meant using part of the gluteus maximus and skin to cover the area.

The old salt seems to have stood up well, but the less experienced doctor became faint and stopped compressing the artery—a most dangerous situation which Tupper corrected by putting his own thumb on it, pushing aside and yelling at his young colleague, who came to his senses and reapplied pressure.

Tupper wrote: “I removed the limb as quickly as possible, picked up the arteries which the sailor ligatured, completed the operation, gave the patient a good dose of brandy and laudanum, after which she said she felt as if she was in heaven, and soon was asleep.”

He added that six weeks later Mrs. Livingston was able to take tea at a neighbour’s house.

Tupper recounts that she “became stout” and passed away four months later while joyfully tending to her garden on a hot day, succumbing to what was then called “apoplexy” (which today would be categorized as a stroke, heart attack, or aneurysm).

Despite being a skilled physician, Tupper is more renowned for his career in politics. He served as Premier of Nova Scotia from 1864–1867, leading the province into Confederation. Tupper also briefly held the position of Prime Minister of Canada, with the shortest term in Canadian history lasting only two months from May 1 to July 8. Despite winning the popular vote by 48 percent to 41 percent in the 1896 election, he lost to Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals who secured 117 seats to the Tories’ 86. Tupper later served as the Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom from 1883–1895.

Tupper’s foray into politics was sparked by a visit from Joseph Howe in 1851. On that occasion, Tupper was tasked with driving out to fetch Thomas Andrew Strange DeWolf, a prominent Halifax Tory figure, for a political event in Amherst. Tupper’s impressive speech led to Howe acknowledging his talent, sparking the movement to draft Tupper as a candidate. Tupper ultimately defeated Howe in 1855 for the Cumberland seat.

Under Johnston’s leadership, Tupper rose in prominence and reshaped conservatism in Nova Scotia by reaching out to the Catholic minority and forming an alliance with Bishop Thomas Connolly in support of Confederation. Tupper also championed the use of steam locomotives and the development of Nova Scotia’s resources for manufacturing.

Religion played a significant role in Tupper’s life, as he came from a Baptist background but later converted to Anglicanism. Despite rumors of being a womanizer, Tupper’s biographer Phillip Buckner dispelled these claims, stating that Tupper was merely flirtatious and had a genuine affection for his wife.

The article’s views are the opinions of the author and may not necessarily align with those of The Epoch Times. Can you please rewrite this sentence?

Source link