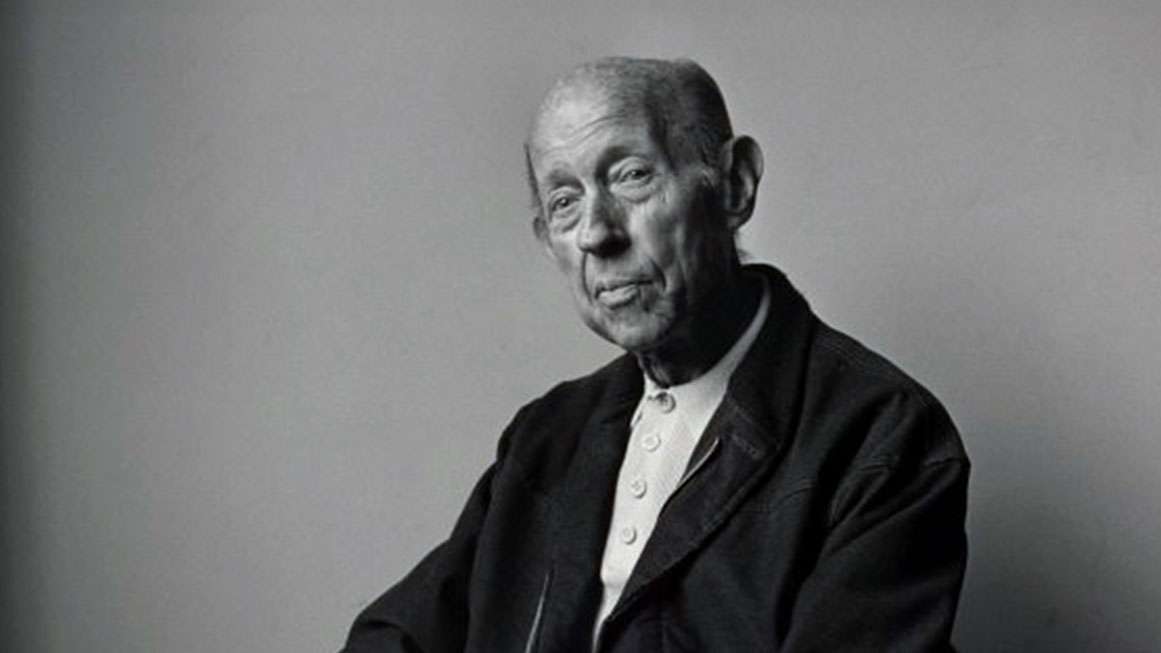

In 1924, on a winter night, a 19-year-old named Dorr Legg had his first sexual experience with another man in a “charming park,” fulfilling a desire he had been studying for years. Born into a Republican family in Ann Arbor overlooking the University of Michigan campus, Legg’s father instilled in him values of self-reliance and individual endeavor, while also teaching him to distrust government and see Democrats as corrupt.

Despite societal views labeling homosexuals as sick or sinful, Legg educated himself on homosexuality through various fields of study and realized he was not alone. However, the criminalization of homosexuality forced him to live a double life, leading to encounters with law enforcement and FBI harassment that solidified his libertarian distrust of the government.

In 1928, Legg moved to New York City and immersed himself in the city’s vibrant homosexual community. Despite his conservative appearance and dislike for flamboyant behavior, he attended drag balls in Harlem and gained new perspectives from black friends and lovers who faced discrimination.

Upon returning to Michigan in the 1940s, Legg’s public outings with black men drew police attention, resulting in his arrest on a charge of “gross indecency.” Outrage at government intrusion led him to flee to Los Angeles, seeking the freedom and tolerance he hoped the city would provide.

However, Los Angeles, like other cities in the 1950s, cracked down on homosexuals, with the police rounding up thousands of individuals based on the belief that they were degenerates. Despite legal challenges, the anti-gay atmosphere drove gay men and women further underground.

On the federal level, both major political parties increased efforts to target homosexuals, with Harry Truman’s administration initiating purges of suspected homosexuals from the federal government in 1950.

Three years later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450, banning homosexuals from working in the federal government, cementing the witch hunt into law. Despite this oppressive environment, the homophile movement emerged, emphasizing love and resistance against societal condemnation of homosexuals. In Los Angeles, landscape architect Legg joined Merton Bird to create the Knights of the Clock, providing support to interracial gay couples. Legg also became a member of the Mattachine Society, the first homophile organization in the U.S., founded by Harry Hay. The society operated as a secret group, discussing civil rights for homosexuals. In response to corrupt police tactics, Legg and others split from Mattachine to form ONE, Inc., launching ONE Magazine in 1953, the first positive coverage of homosexuality in the U.S. Legg, now known as William Lambert, dedicated himself to promoting the magazine and advocating for gay rights, using pseudonyms to protect his identity. Despite government crackdowns on homosexuality, ONE Magazine gained thousands of subscribers and became a platform for LGBTQ voices in a hostile society. More than half of ONE’s subscribers paid an extra dollar on top of the $2 annual subscription fee to receive their magazines in a discreet, unmarked envelope. However, due to the lack of protection for homosexuals from intrusive vice squads, it was unlikely that their mail would remain unopened. The Comstock Act of 1873 prohibited the mailing of anything deemed lewd or obscene, putting ONE at risk of being censored. Despite facing challenges from the post office, the magazine’s founder, Legg, refused to be silenced and fought back against government censorship.

Legg’s defiance of government interference extended to a court case that dragged on for years, ultimately resulting in a landmark Supreme Court decision in favor of ONE’s right to publish freely. This victory marked a significant milestone for the homophile movement in the United States. Legg’s commitment to challenging oppressive authorities and advocating for the rights of homosexuals was a driving force behind his actions.

Despite the progress made, Legg continued to push for greater acceptance of homosexuality and the recognition of homosexuals as equal citizens under the law. He believed in the importance of standing up against government intrusion and discriminatory practices, even if it meant going against his own political party’s agenda. Legg’s views on civil liberties and individual freedoms positioned him as a champion for the rights of homosexuals in a time of increasing government scrutiny and persecution. He proposed that the 1961 ONE Midwinter Institute, an annual gathering of three homophile groups, could focus on drafting a “Homosexual Bill of Rights.” Legg believed this would not be controversial among homophile activists, as it was an early example of identity politics that would later be embraced by gay liberationists. However, in 1961, Legg’s proposal faced opposition due to disagreements over politics and strategy.

The planning meeting for the conference almost fell apart as participants could not agree on the meaning of words like “liberty, rights, freedom, [and] free-will.” Del Martin, in The Ladder, warned that publishing a bill of rights could set the homophile movement back by demanding rights that may never be granted. At the Midwinter Institute, Jaye Bell expressed concerns that a Homosexual Bill of Rights could be dangerous and advocated for a gradual approach through education to change perceptions about homosexuals.

Despite Legg’s efforts, a Homosexual Bill of Rights was not established. This led to tensions within the homophile movement, with Legg expressing frustration towards lesbians for their lack of understanding of the struggles faced by homosexual men. The fallout over the bill of rights highlighted the growing divide between ONE and the DOB, as well as strained relations with Mattachine.

As the New Left and Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, homophile organizations shifted towards political activism and minority rights advocacy. Meanwhile, Legg became involved in founding gay Republican clubs to make their presence known in the GOP. By the 1980s, he was a founding member of the Log Cabin Club, which later evolved into the national Log Cabin Republicans organization.

Legg lamented the focus on the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion as the starting point of the gay rights movement, overlooking the decades of hard work by earlier activists. He expressed concerns about the direction of the movement aligning with left-leaning issues and organizations. Despite his reservations about the direction of the gay rights movement and the Republican Party, Legg remained committed to advocating for limited government, personal privacy, and individual freedom. Please rewrite this sentence.

Source link