Commentary

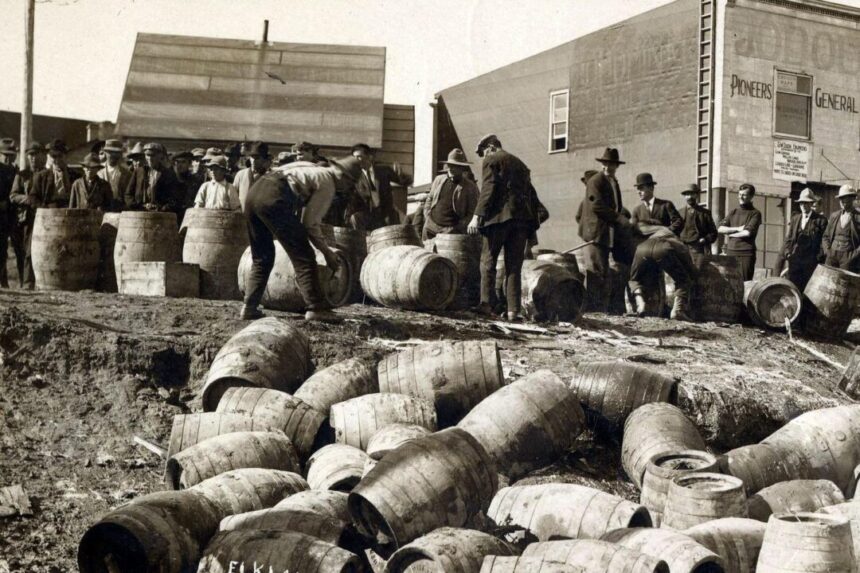

Temperance activists from Victorian times to the interwar years strove to reduce or ban drinking in Canada, with mixed success.

Any reader who follows the news will see reports from time to time of some new study about drinking less alcohol to reduce the risk to health and long life. The

official guidance in Canada is to limit daily intake to one pint of beer, one glass of wine, or a gin and tonic—provided you sometimes skip a day. Of course, this is simply “advice” Canadians are free to ignore—and many do.

In Canada, the movement to prohibit drinking alcohol peaked between Victorian times and World War I. It was led by small groups emerging from some Protestant congregations all across the country. In 1875, hundreds of them met in Canada’s metropolis of Montreal to establish a national movement. They called themselves the Dominion Prohibitory Council, changing their name a year later to the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic.

There were many overlapping groups and activists like them and some drew real or imagined linkages between alcoholism, immigrant ghettos, syphilis, and the need for sterilization and

eugenics to ensure a “healthier” population and “race betterment,” and to avoid “mental bankruptcy.” What they fought for was a real mixed bag: temperance, hygiene, sex education, “birth control,” and selective breeding to weed out bad genes, all, of course, in the name of “science.”

These dedicated activists, seeking to change the laws in order to improve the behaviour of others, like the interrelated movements such as women’s votes and

eugenics, were mostly limited to English Canada, which had Protestant denominations that forbade drinking. Thus, like birth control and selective breeding, the temperance movement never really took off in Quebec until after World War II. In that province, the French majority’s Catholicism enjoined moderate enjoyment of alcohol—a little “wine maketh glad the heart of man,” said the psalmist.

In English Canada temperance grew out of progressivism and the Social Gospel, informed by the belief that drinking alcohol is contrary to the will of God. While immoderate by most people’s standards, temperance is intended as a safeguard for purity and the health of family and public life. Activists in Victorian and Edwardian times, for example, pointed to the bad social impact of excessive drinking, the related problem of gambling, and their corrupting effects on immigrants or the working class, or on men generally.

By contrast, other cultures accord alcohol a role in their religious rituals. In Japan, the Shinto tradition includes “omiki,” sacramental sake. Judaism incorporates ritual wine in the Passover Seder meal, and that is partly why Roman Catholics use wine in their Mass. Moreover, they regard wine as a metaphor for the transformation of hearts.

Indeed, the wine used in a Mass must contain alcohol according to church law. In the Gospel of John, chapter 2, Jesus attends a wedding and turns water into wine. According to St. Chrysostom, the meaning of this action was to show that the weak love and will of ordinary men (symbolized by plain water) can be

changed by consistently relying on God (symbolized by the wine).

And thus, in the national referendum on drinking in 1898, over 81 percent of Quebecers voted against prohibition. Accordingly, the temperance organization called La Ligue Anti-alcoölique did not even try to prohibit alcohol, only to moderate its use and to strengthen family life.

Actually, the first temperance efforts in Canada were by Catholic priests trying to protect indigenous people from unscrupulous traders selling alcohol to them. This protective approach was typical of the Catholic Church’s relationship with the indigenous for the next four centuries, despite disinformation and

myths. In 1661, the great Monsignor Laval, the first Bishop of Quebec, convinced government authorities that they should pass a law against giving liquor to the native people. They did and they meant it: the penalty was death! In due course, two lawbreakers were shot and another flogged.

Later in 19th- and 20th-century English Canada, women were especially prominent in the temperance movement, forming the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1874, a vivid expression of Protestant strictures which was, interestingly, allied to the movement for women’s suffrage (right to vote). The wider movement succeeded in getting the Alexander Mackenzie Liberal government to pass the

Canada Temperance Act, better known as the Scott Act, which enabled local governments to hold votes to enact grassroots prohibition. But advocates still persisted and some got stricter laws passed at the provincial level.

Many of the same figures who advocated women’s votes also strove to ban drinking. Louise McKinney, born to a Methodist family in

small-town Ontario, eventually settled with her husband in the Canadian West in 1903, rose through the ranks of the WCTU, and helped to establish 40 branches. Mrs. McKinney became the first woman in the British Empire elected to a legislature, sitting as an Alberta MLA from 1917 to 1921.

Shortly after that, most Methodists merged with other idealistic Protestants into the United Church of Canada and McKinney became a lay preacher in that body. She went on to be one of the

Famous Five, advocates for women’s rights who are commemorated by dramatic statues near Parliament Hill in Ottawa. (Though the Famous Five supported eugenics and race purity, no one has defaced or smashed those particular statues.)

Even with all that, prohibition was much more successful in the United States than Canada.

Due to Quebec’s strong dissent, the federal government proceeded cautiously, shifting the focus from alcohol itself to the distribution of powers between Ottawa and the provinces. The question arose: which level of government should have the authority to decide such matters?

During wartime, prohibition laws had a finite duration. In 1919, the power to regulate alcohol returned to the provinces, allowing them to conduct referendums. This approach was deemed sensible, as in a federation, it is typically the local authorities closest to the people who should make such laws.

By the late 1920s, temperance had fallen out of favor, coinciding with the increasing suffrage of women and a decline in anti-alcohol sentiment. Despite this shift, the legacy of temperance endured in the form of strict regulation and quasi-monopoly control of liquor by provincial bodies such as the LCBO, the BC Liquor Commission, and the SAQ in Quebec (formerly the Quebec Liquor Commission).

This demonstrates that even though Quebec rejected prohibition, the province’s inclination towards state intervention and regulation remained strong.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.