Commentary

“Not a day passes when, reflecting on what I have been, I do not see in my mind’s eye the rock where I was born, the room where my mother inflicted life on me, the raging tempest that was my first lullaby …. Heaven itself seemed so to arrange these circumstances to place in sight of my cradle an emblem of my destinies.”

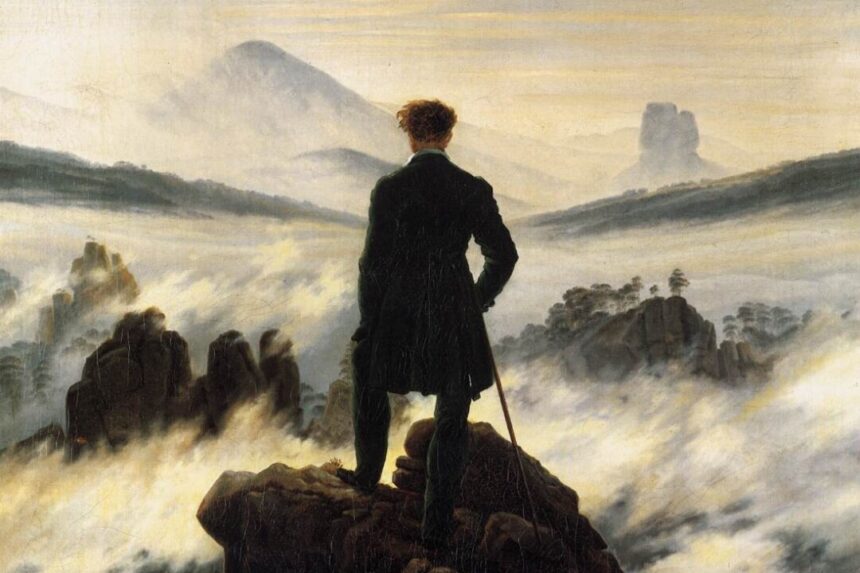

“The Monk by the Sea” by Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840). Alte Nationalgalerie, Public Domain

Caspar David Friedrich’s life spanned an era of revolutionary quests for political liberty and a reaction which sought an internal, spiritual liberty away from the violence of politics. He was born in 1774 on the Baltic coast of Swedish Pomerania (now Germany), and he spent most of his life in Dresden, where he died in 1840. Friedrich rose to prominence as an artist in the first decade of the 19th century with large-scale watercolor and pencil drawings of landscapes imbued with a mystical spirituality. He was a perfect exemplar of the original generation of sensitive young men.

The year Friedrich was born, Goethe published “The Sorrows of Young Werther,” a proto-Romantic novel about a painfully sensitive young man who, following a sketching holiday in nature, is so overcome with unrequited love that he commits suicide. The success of the book was so immense that it led to international “Werther Fever,” which caused young men to dress like the hero and even, reportedly, to commit copycat suicides.

Friedrich was a teenager at the time of the French Revolution, in which the German-speaking Queen of France was, from the perspective of traditional Europe, violently murdered in an act of martyrdom to the Catholic Church and the traditional family. Following the French Revolution, the artistic and intellectual youth of Europe divided along political and aesthetic lines. Some young people became revolutionaries; others, like Friedrich, became Romantics. They rejected both contemporary revolutionary politics and older Enlightenment values: Catholicism was preferable to Protestantism, pirates to merchants, the moon to the sun, a violent storm to a clear sky, and the crooked way to the straight path.

Friedrich’s early drawings and watercolor paintings, well-represented in this exhibition, show a focus on explicit depiction of religious icons, which will evolve in his later oil paintings to a focus on nature itself. A portent of his future direction, the ca. 1799 watercolor sketch “Figures Contemplating the Moon,” depicts two figures turning away from the large cross and church to admire a full moon, partially hidden between dramatic clouds.

We see the young artist developing a clear iconography and compositional style: most often, a mountain rises at the center of the work of art, with a cross or statue of the Virgin at its pinnacle. In the distance, pine covered hills rise and fall to an obscure background in which sea, sky, and mountains merge.

“The Cross in the Mountains,” from 1806, is a gorgeous example of his early mastery. A central peak is crowned by a life-size crucifix and back-lit pines. Beyond it is a turbulent sky which glows in the supernatural manner Friedrich is able to conjure from mere paper, brown watercolor, and pencil. Friedrich later adapted this drawing into an altarpiece, which caused a scandal at the time–its mixture of religious and natural imagery was thought by many to be sacrilegious.

By the time the viewer arrives at the pinnacle of the show, the cross has been replaced with the selfie. Friedrich’s most famous painting, “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog,” painted in 1817, is the kind of painting that is so famous it is hard to see clearly. First, because on both of my visits, the view was blocked by a crowd of people whose backs mimicked those of the wanderer, although their raised iPhones did not. Second, because the painting has become a meme rather than a work of art. It is hard to look at it without thinking of the many reproductions, parodies, and posts it has inspired.

At the center of the painting, a man very much like Friedrich in age, build, and blondness stands with his back to the viewer, his feet planted on a rocky peak, looking down into a misty valley from which spooky rocks, pines, and mountains rise. A wall text informs us that the motif of the figure depicted from behind was known as the Rückenfigur and was meant to “prompt viewers’ imaginative engagement with the landscape.” If you have ever opened Instagram, you have seen many conscious and unconscious imitations of this painting, usually featuring shapely young women in yoga pants rather than men in green velvet suits. The engagement they are hoping to prompt from viewers is, I think we can assume, not with the landscape. Indeed, there are several Rückenfigurs in this exhibition depicting the artist’s wife, Caroline.

While she possesses the same beauty as any modern influencer, the portrayals lack the grandeur of the “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich. What can we glean from Friedrich’s painting? Is the young man a wanderer lost in the uncertainties of the 19th century, with ideologies shifting and individualism rising? Is his journey the destination itself? As he gazes out from the cliff, is he contemplating beauty, nature, or something darker? Or is he, like today’s selfie-takers, simply marking his presence? The exhibit “The Soul of Nature” not only evokes present-day imagery and political currents but also harks back to a deeper past, nestled among Greek and Roman sculptures. The medieval elements in Friedrich’s paintings, with young men in anachronistic costumes, challenge societal norms of the time. The roots of landscape painting in Europe trace back to the late medieval period, where artists disguised nature within saintly narratives. This ambiguity of anachronisms is a modern concept, mirroring the iconographic battles of the past. Friedrich’s work continues to hold relevance today, influencing contemporary art and cinema. As the world transitions into a new era of technology and information, artists seek inspiration from the past to navigate the complexities of the present. The legacy of artists like Friedrich offers hope for creating a vision that transcends the tumultuous currents of history. Please rewrite the following sentence for me.

Source link