Commentary

“Art is neither moral nor immoral; it’s just art.” This idea has been a common refrain throughout my research and writing on the Motion Picture Production Code. It suggests that art, whether in the form of a painting, a play, or a film, exists outside the realm of morality. Those who advocate for this view often use it to push back against religiously motivated attempts to regulate entertainment, arguing that art should not be subject to moral judgment.

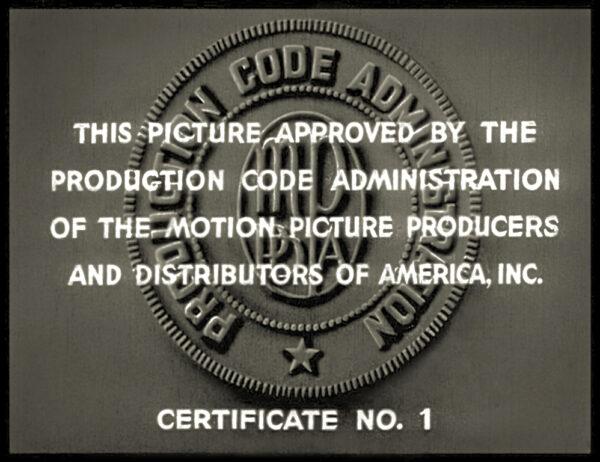

This argument is particularly relevant when discussing the Production Code, also known as the Hays Code, which was closely associated with the Catholic Church. Established in 1930, this set of guidelines for film content governed Hollywood’s moral standards from 1934 until it was replaced by the modern Rating System in 1968. Initially, the Production Code Administration (PCA) rigorously enforced these standards due to strong leadership. However, in the following years, lax enforcement led to a decline in adherence to the Code.

While Easter has passed, the season of Resurrection is ongoing for Christians. This presents an opportune moment to delve into the moral implications of this issue.

Immoral, Amoral, Unmoral, Nonmoral

When considering the morality of films, it is essential to understand the terms used to discuss morality. According to the Third Edition of “The Reader’s Digest Great Encyclopedic Dictionary” from 1969, “immoral,” “amoral,” “unmoral,” and “nonmoral” all signify a lack of moral values. An immoral person knowingly violates moral principles, while an amoral individual lacks a sense of right and wrong and may act contrary to morality unintentionally. Unmoral and nonmoral indicate actions or entities that fall outside the realm of morality. For instance, a baby is unmoral, while meteorology is a nonmoral field of study.

Based on these definitions, films themselves are unmoral as they are inanimate objects. Art, including films, lacks inherent morality and cannot be deemed immoral or amoral. However, no work of art can be considered nonmoral. Art, being a product of human imagination, reflects the creator’s mind and soul. It serves purposes such as entertainment, education, inspiration, and pleasure for audiences. Stories depicted in films, whether real or fictional, aim to evoke emotions and thoughts in viewers. While the film as a medium may not possess morality, its content can contain immoral elements that may elicit immoral responses.

Throughout history, individuals, including politicians, clergy, and concerned citizens, have sought to impose various forms of censorship on art and literature, particularly in Western Christian societies, to safeguard public morality and prevent corruption, especially among vulnerable populations. As society has become more secular, these efforts have been criticized as attempts to stifle creativity and expression. This debate prompts us to examine the origins of one of the most influential moral frameworks in the arts, the Motion Picture Production Code.

A Christian Background

The Motion Picture Production Code was authored by Martin J. Quigley and Father Daniel A. Lord. Quigley, a publisher of motion picture trade publications in Chicago, maintained a strong commitment to his Catholic faith outside of his professional duties. While his work was primarily secular, his Christian values were evident in his writings. As early as 1915, he expressed concerns about censorship in silent films and proposed that adherence to a decency standard could prevent such artistic compromises.

Quigley’s idea gained traction in 1929 when Chicago Catholics protested against the controversial film “The Trial of Mary Dugan.” In response to calls for boycotts and censorship, Quigley proposed a Code to regulate film production as a practical solution. This concept was well-received by a group of moral-minded Catholic individuals, leading to the collaboration between Quigley and Father Lord, resulting in the Motion Picture Production Code of 1930.

The Code was submitted to Will H. Hays, the head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA).

Martin Quigley’s initiative took shape in response to the outcry over “The Trial of Mary Dugan” in 1929, showcasing a proactive approach to addressing moral concerns in filmmaking. This led to the collaboration between Quigley and Father Lord, resulting in the creation of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1930 as a guideline for movie production.

The finalized Code was presented to Will H. Hays, the head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA).

Hays, known as the Czar of Hollywood, led the MPPDA since its establishment in 1922. Movie executives saw his political background as a way to address public backlash against the film industry following scandals in the early 1920s. However, his public relations skills did not lead to significant change. When Martin Quigley presented the Production Code to him, Hays embraced it as the solution to the industry’s problems.

The Code, initially known as the Hays Code, was presented by Hays himself to Hollywood and the public. He believed it would be better received if attributed to a Presbyterian like himself rather than a group of Catholics, given the sentiments towards the Catholic Church at the time. The Code aimed to establish rational moral principles accepted by reasonable, decent individuals, regardless of religious affiliation.

While the Code and film censorship have waned in popularity, individuals who value traditional values can appreciate its content. Christians from various denominations have debated whether entertainment falls under religious jurisdiction. The answer, perhaps, lies in Philippians 4:8 of the King James Version of the Bible, which encourages focusing on things that are true, honest, just, pure, lovely, of good report, virtuous, and praiseworthy.

Source link